Malware Analysis - Zeus Banking Trojan

This documentation provides a detailed guide on the techniques and tools used to analyze the behavior, characteristics, and mitigation strategies of a Zeus Trojan Banking virus in a controlled environment.

Objective: Analyze a piece of malware. Document process of unpacking, analysis, and understanding its mechanism

Outcome: Detailed report that walks through analysis, findings and tools used. Highlights malware research skills and ability to communicate technical findings

Malware sample: Zeus Banking Trojan

VM Setup

- Isolation: Ensures malware is contained within the virtual environment, safeguarding host network and system from potential malware escape and contamination

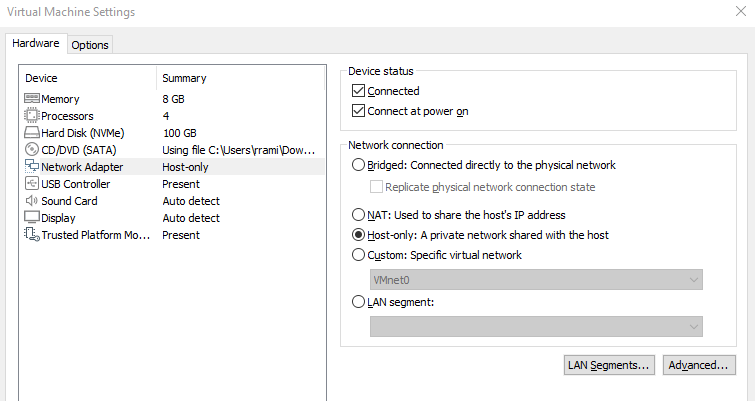

- Ensure VM network settings are set to: NAT or Host

- Set to Host once malware detonation occurs

- Disable shared folders between host and VM

- Ensure VM network settings are set to: NAT or Host

- Snapshots: Allows quick recovery by creating VM backups before key analysis phases, enabling easy rollback to prior states.

Network Topology

- VMWorkstation: Virtualization software hosting two virtual machines: Windows 11 and Remnux

- Windows 11 - Malware execution/analysis

- REMnux- INetSim configuration

- Host only configuration if possible

Tools

- Static Analysis

- Virustotal: A free online service that analyzes suspicious files and URLs to detect types of malwares by aggregating multiple antivirus products and online scan engines

- PeStudio: Tool that allows malware researchers to inspect the inner workings of executable files without running them, highlighting potential security flaws, suspicious sections, and indicators of compromise

- Floss: Utility designed to automatically de-obfuscate strings from malware binaries; can help identify hidden C2 servers, malware configurations, and other indicators of compromise

- Capa: Tool that detects capabilities within executable files; uses rule-based system to identify and classify a wide range of behaviors in binary programs

- Cutter: Tool that is designed to facilitate static analysis of malware by providing disassembly, graphing, scripting, and debugging capabilities

- Ghidra: Provides capabilities for disassembling, decompiling, analyzing, and debugging software across multiple platforms; widely used for malware analysis

- Dynamic Analysis

- Inetsim: Software suite for simulating common internet services in a lab environment; allows analysts to observe malware interactions with simulated network services

- Wireshark: Network protocol analyzer that captures and interactively displays the traffic running on a computer network; essential for understanding network-level activities of malware such as data exfiltration and command and control communications

- Procmon: Short for Process Monitor, a tool that monitors and records real-time file system, registry, and process/thread activity in Windows environments

- Identification and classification

- YARA: Tool designed to identify and classify malware samples according to textual or binary patterns, making it easier to detect and analyze new samples that belong to known families

- Hybrid Analysis: An online platform for automated malware analysis, offering a combination of static and dynamic analysis techniques to provide insights into the behavior and characteristics of suspicious files. It assists in identifying and understanding malware threats by analyzing their code and execution in a controlled environment.

Setup

For this project VMWorkstation will be used for our virtual environments. VMWorkstation allows for easy installations of the environments and the creation of networks for the analysis of malware. Both Windows 11 and REMnux are compatible with this software.

Most tools being used in this analysis will be used in the Windows environment, which can easily be obtained by setting up Flare VM in said environment.

FlareVM is a Windows-based security distribution designed for malware analysis, incident response, and penetration testing. It comes pre-configured with a variety of tools and utilities specifically tailored for these tasks, streamlining the analysis process.

Before installing FlareVM via PowerShell, we must tweak the Windows Defender Settings, which can interfere with the installation. This consists of deactivating Windows Security through various means, by editing the registry editor.

Once Windows Security has been disabled correctly, we can download and install FlareVM:

## In Powershell admin prompt run:

(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadFile('[https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mandiant/flare-vm/main/install.ps1](https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mandiant/flare-vm/main/install.ps1)', "$([Environment]::GetFolderPath('Desktop'))\install.ps1")

## Change directories to the desktop

cd C:\Users\<USER>\Desktop\

## Unblock downloaded files

Unblock-File .\\install.ps1

## Run file

Set-ExecutionPolicy Unrestricted

## Choose "Y"

.\\install.ps1

## Setup can take a while depending on your system specs

## FLARE VM Install Customization menu will appear, feel free to adjust installation folders, and wanted packages

While FlareVM is installed, we can begin to setup Remnux.

REMnux is a Linux distribution focused on reverse-engineering, malware analysis, and threat intelligence tasks. It provides a curated collection of tools and scripts to assist analysts in dissecting and understanding malicious software and related artifacts.

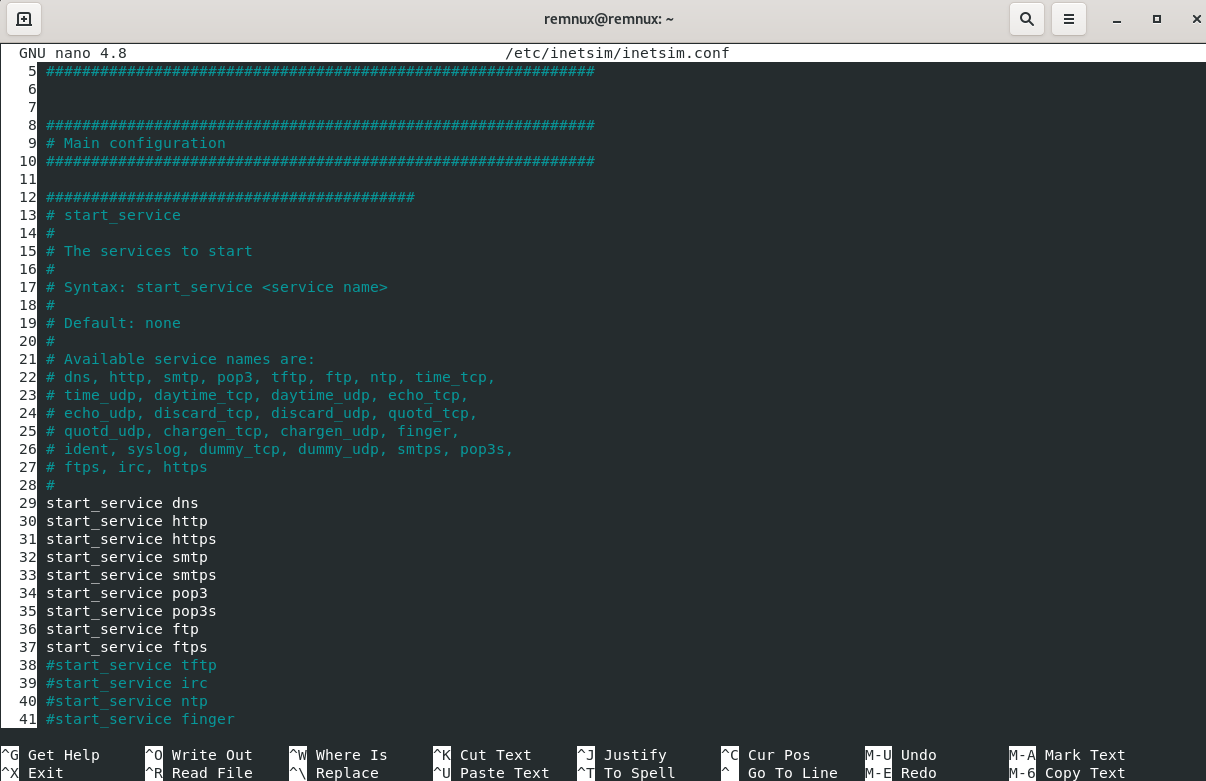

Various tools are offered within REMnux, but for the purposes of this project, INetSim will be the main tool we will use. INetSim simulates common internet services to observe malware interactions with said services, meaning that we must configure our INetSim to simulate certain services within the corresponding networks.

Creating a host-only network environment within VMWorkstationPro is straight forward: all that must be done is to configure the Network Adapter setting to Host-only on both virtual machines within the respective settings. Specific virtual networks can also be created if need be, with further configuration.

Once a host-only configuration has been enabled, INetSim must be configured properly within the REMnux virtual machine:

## First we edit the INetSim configuration file

sudo nano -l /etc/inetsim/inetsim.conf

First, we must uncomment start_service dns so that we can make use of the simulated DNS settings that INetSim provides:

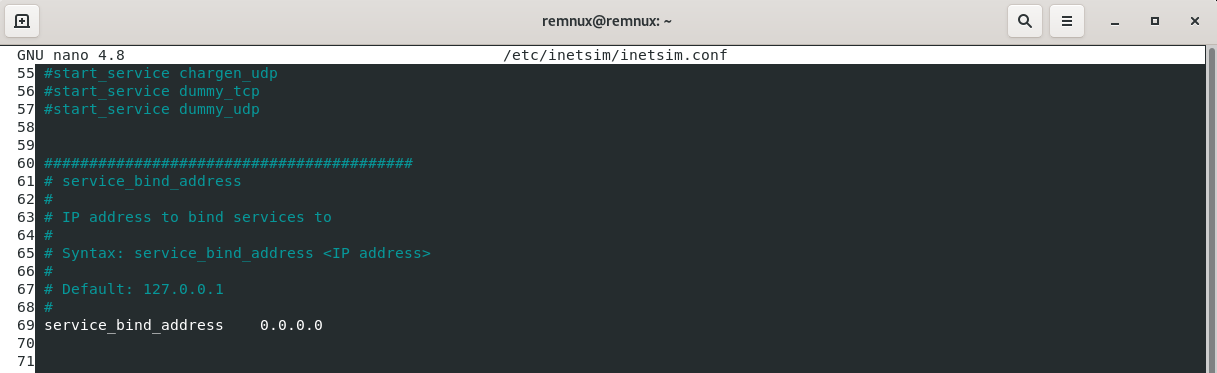

Second, we can uncomment and adjust the service_bind_address:

The service_bind_address parameter in the INetSim configuration file specifies the IP address to which INetSim will bind its fake services. When set to 0.0.0.0, it means that INetSim will make its fake services available to any IP address it can communicate with, effectively binding to all available network interfaces on the machine. This allows INetSim to accept connections from any IP address, making its fake services accessible from any network the machine is connected to. If need be, a specific IP address can be input into the service_bind_address .

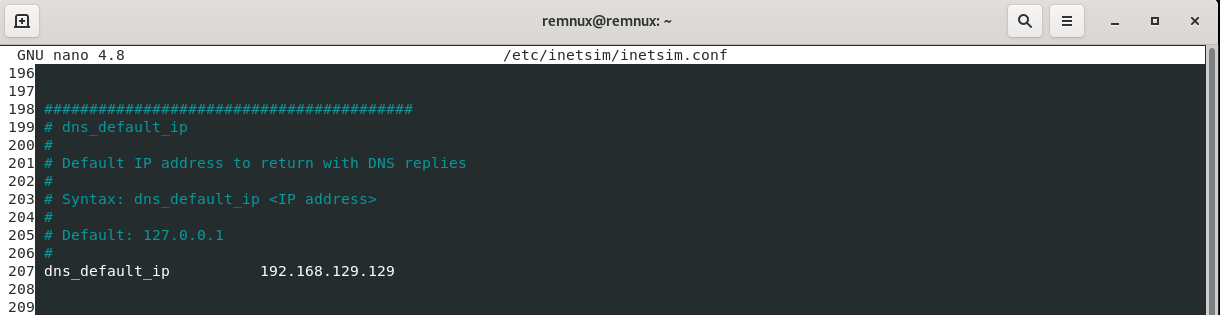

Third, we can uncomment and adjust the dns_default_ip :

In this instance we must input the IP address of the virtual machine that will be running INetSim. This means that all DNS queries will be redirected to the REMnux machine.

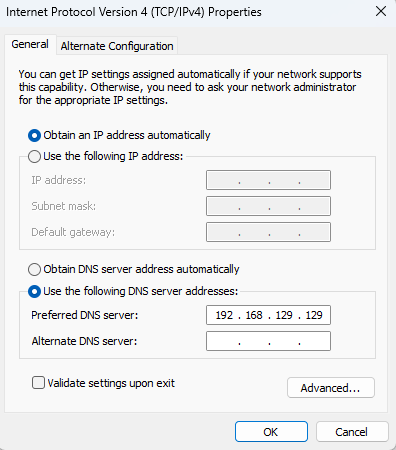

Now we can change back to our Windows virtual machine to ensure that it uses our REMnux machine as its default DNS server. This can be done by configuring IPv4 properties:

To ensure communication between the two virtual machines we can ping the corresponding IP addresses from each machine.

Zeus Banking Trojan Report

For this project we will be performing some basic static and dynamic analysis of a malware known as the Zeus Banking Trojan. While many versions of this malware exist, we will focus on a sample dated November 26, 2013, which is likely to be one of the iterations of the Zeus Banking Trojan: the Gameover Zeus.

Gameover Zeus, also known as P2PZeus or GOZ, was a notorious type of malware that first emerged around 2011. It was a variant of the Zeus Trojan, which primarily targeted Windows operating systems. Gameover Zeus was designed to steal sensitive information, such as banking credentials, from infected computers. It operated through a peer-to-peer (P2P) network, making it more resilient to takedown efforts compared to its predecessors.

One of the most significant features of Gameover Zeus was its ability to create a botnet, a network of infected computers controlled remotely by cybercriminals. This botnet could be used to carry out various malicious activities, including distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, sending spam emails, and spreading additional malware.

To conduct an analysis, we will oversee four key sections: Fingerprinting, basic static analysis, advanced static analysis, and classification and identification with YARA and Hybrid-Analysis.

Fingerprinting

Fingerprinting is the initial phase of malware analysis, crucial for gathering identification details like file hashes and metadata. These attributes distinguish the malware from benign files and lay the foundation for further analysis. In this section, we explore the techniques used to extract and interpret these vital identifying features, essential for understanding malware’s behavior.

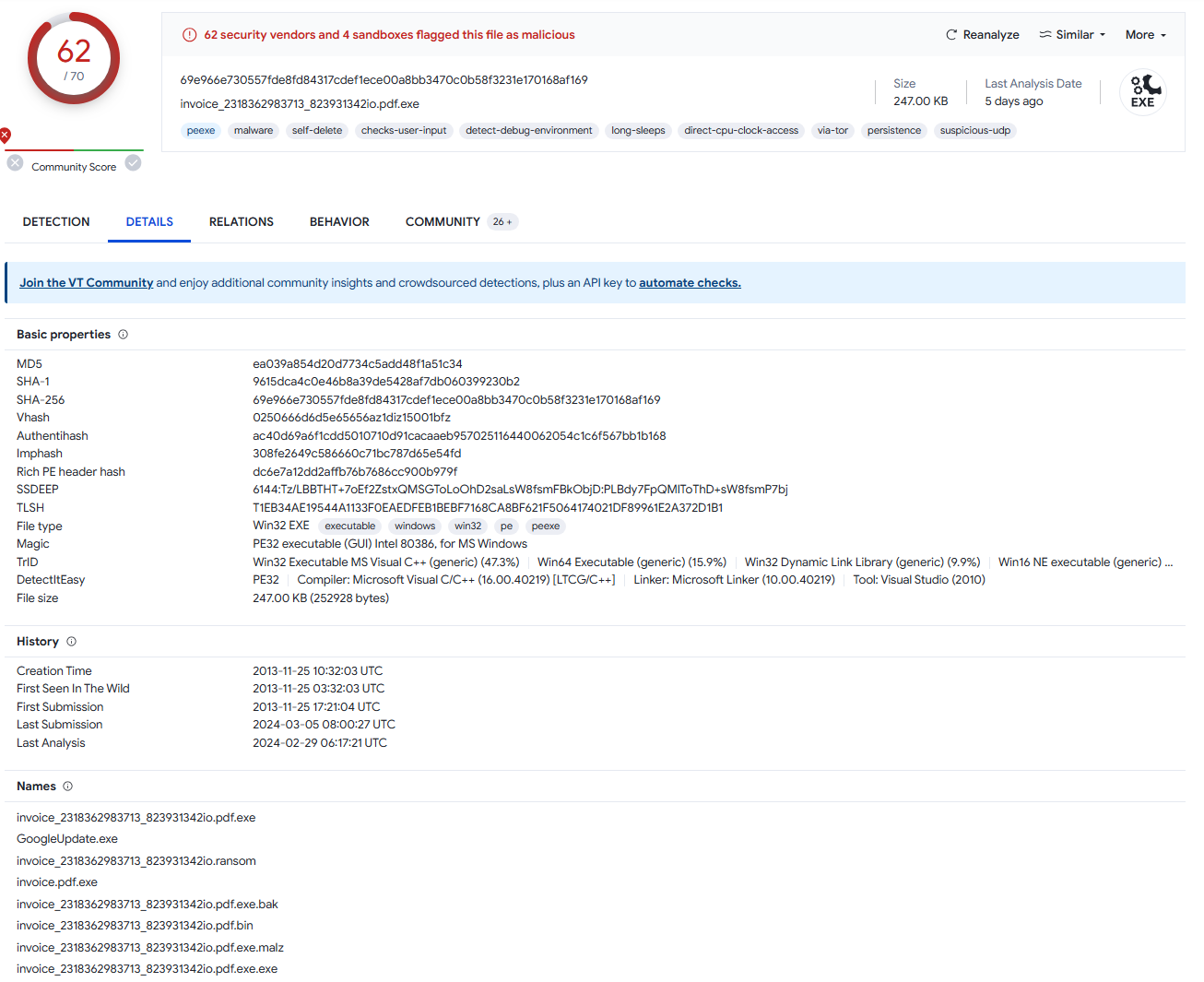

In the fingerprinting stage we can leverage [VirusTotal](https://www.virustotal.com/gui/home/upload), an online platform renowned for its aggregation of multiple antivirus engines and other detection mechanisms. VirusTotal allows us to upload suspicious files, triggering a comprehensive analysis that scanned it for known malware signatures and suspicious behaviors. Through this process, we obtained a detailed report comprising detection rates, file hashes, and metadata, providing valuable insights into the potential threat level of the file and serving as a foundational step for further analysis:

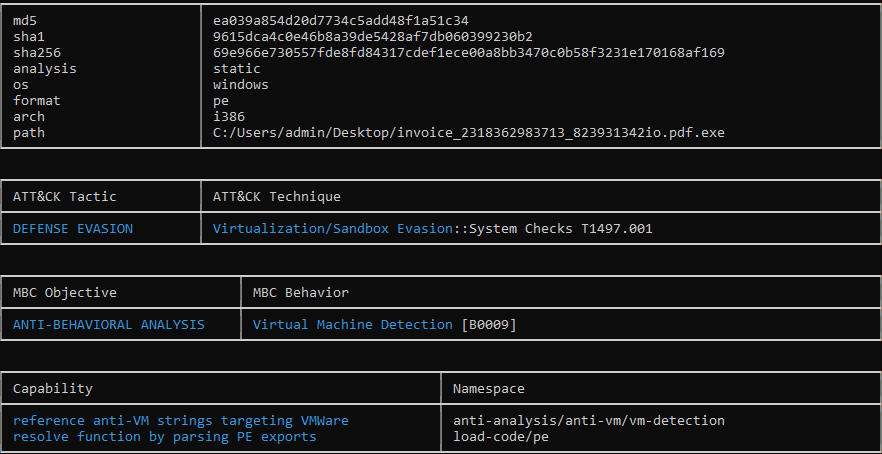

File name: invoice_2318362983713_823931342io.pdf.exe

VirusTotal not only provides security vendors’ analysis, but also some basic properties such as hashes:

- MD5: ea039a854d20d7734c5add48f1a51c34

- SHA-1: 9615dca4c0e46b8a39de5428af7db060399230b2

- SHA-256: 69e966e730557fde8fd84317cdef1ece00a8bb3470c0b58f3231e170168af169

Hashes play a crucial part in the fingerprinting stage due to their ability to uniquely identify files based on their content. These cryptographic hash values allow us to compare the hash value against known malware signatures, which in turn facilitates rapid identification and categorization of the file. Additionally, we can verify file integrity and detect any modifications or tampering through these hash values.

Basic Static Analysis

Basic static analysis represents the initial examination of a malware file’s structure and content without execution. By scrutinizing headers, strings, and other attributes, analysts gain fundamental insights into the malware’s purpose and potential impact. This phase is critical for detecting patterns of obfuscation and identifying indicators of malicious intent. In this section, we delve into basic static analysis techniques, essential for laying the groundwork for deeper investigation into the malware’s functionalities and behaviors.

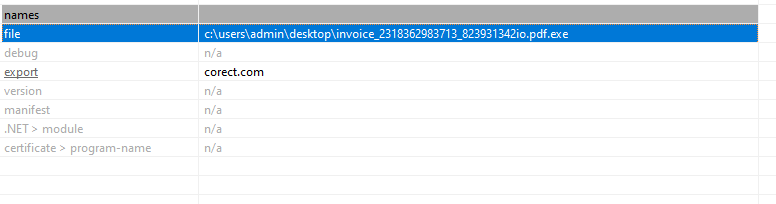

Pestudio is a powerful tool for basic static analysis of malware, providing insights into a file’s characteristics without execution. By examining file headers, strings, and embedded artifacts, Pestudio enables analysts to uncover potential indicators of malicious intent and identify patterns of obfuscation or suspicious behavior. For example, on the main assessment page we can see that there is a URL in the export section. This could indicate that the executable file that we are assessing interacts with or references resources hosted at those URLs:

However, following up on this URL does not yield any interesting results.

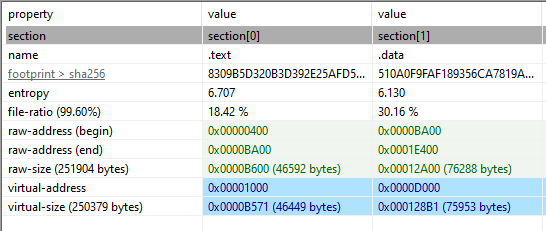

Pestudio also contains a “sections” tab that provides more information on the internal structure of the Portable Executable file being analyzed. In the following image we want to focus on entropy, raw size, and virtual size. These three fields can help point to whether the file contains encrypted or compressed data, which could be a sign of obfuscation or anti-analysis techniques. A high entropy value would point to compressed or encrypted data, as would a large disparity between the raw size and virtual size:

An entropy value of 6.707 is not necessarily concerning when it comes to a coding section (.text), but when it comes to a data section, which might be more unusual, potentially pointing to malicious code.

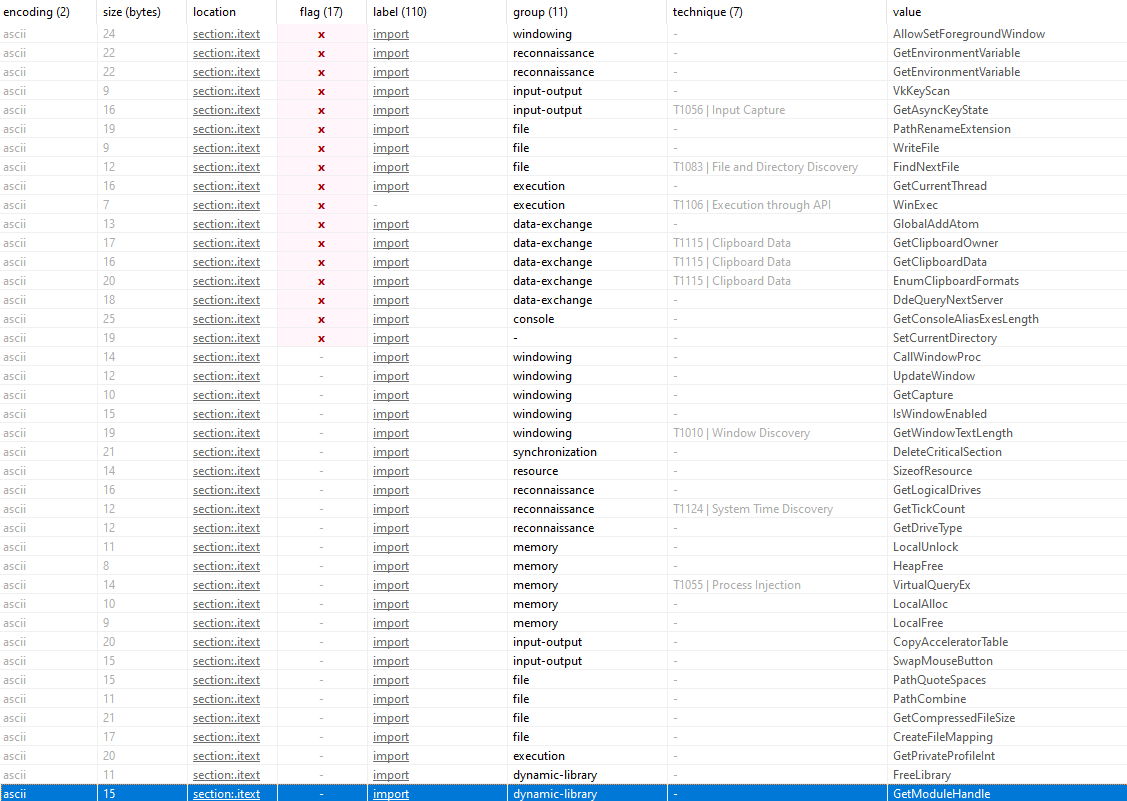

Next, we will look at the “strings” section. The strings section offers valuable insights by displaying ASCII and Unicode strings extracted from the analyzed file.

This can help us identify plaintext strings embedded within the file, including function names, registry keys, URLS, and other potentially suspicious or informative data. Further examination can provide initial clues about the file’s functionality, intentions, and potential connections to known malware behavior.

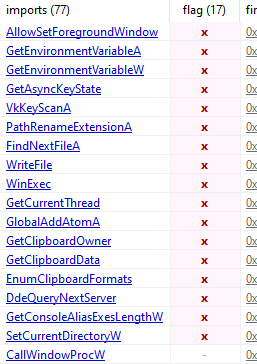

Take for example the values on the far-right column, where we can see various function calls that could elucidate the file’s behavior. PEstudio also flags certain functions that could be problematic, such as “GetClipboardOwner”, “WinExec”, “WriteFile”

GetClipboardOwner: This function retrieves the handle of the window that currently owns the clipboard. This could be used to determine which application currently has data stored in the clipboard, potentially extracting sensitive informationWinExec: A deprecated function in the Windows API that launches an application and reutrns its instance handle. Malware often uses this function to execute other programs or commandsWriteFile: Windows API function used for writing data to a file or an input/output device. It can be used to write data to files on disk, such as log files, configuration files, or payloads.

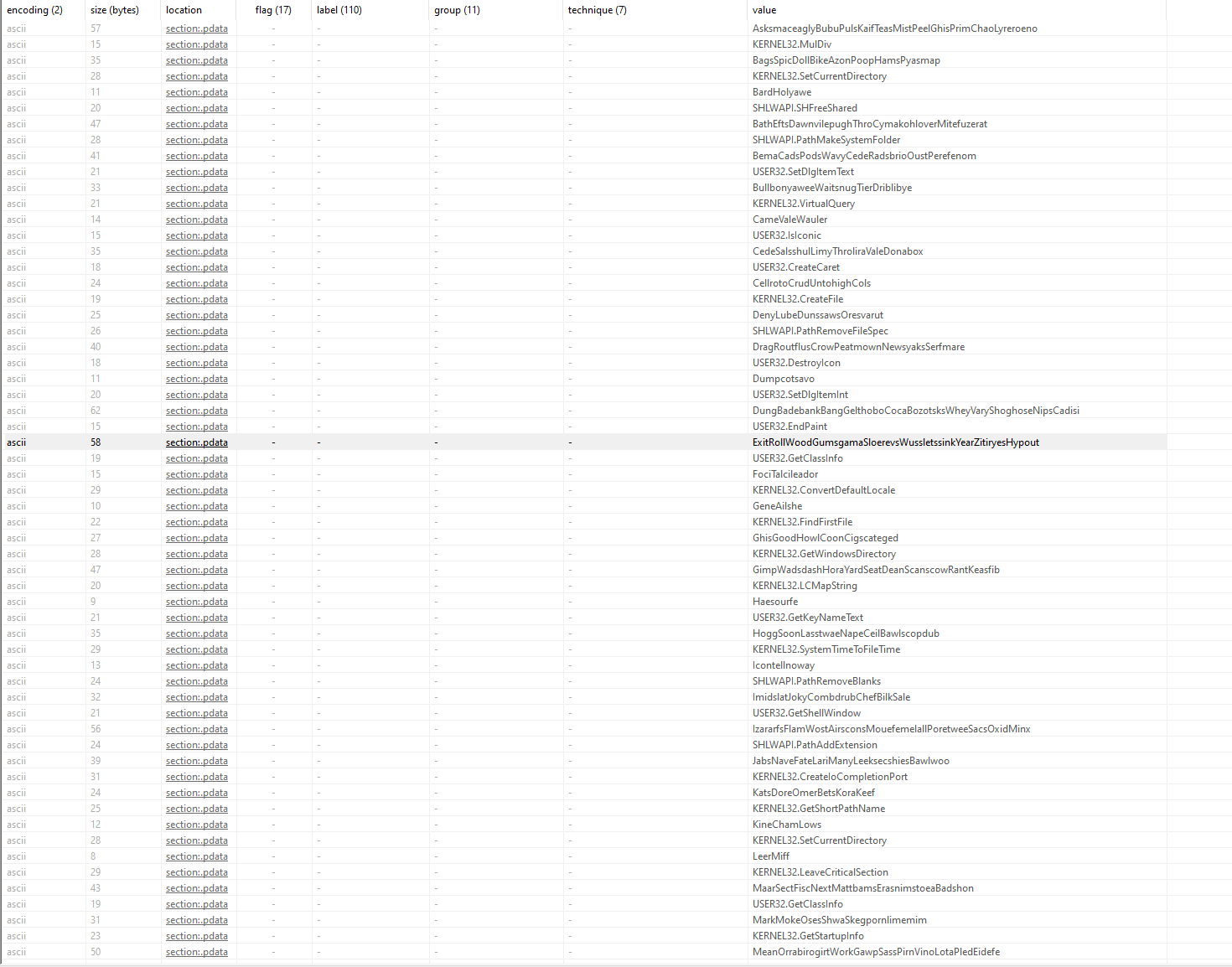

Furthermore, the following values also point to potentially malicious code:

What we see in the image is a set of random values followed by a function. This happens repeatedly for many values which could point to code obfuscation. This is when malware authors employ obfuscation techniques to make their code more difficult to analyze and understand. Random strings interspersed with functions could be part of an obfuscation strategy aimed at disguising the true functionality of the code. This could also be an indicator of using dynamic function resolution techniques to evade static analysis. Instead of calling functions by name, malware might construct function pointers or use other methods to resolve function addresses at runtime. In such cases, the random values could be data used in the resolution process.

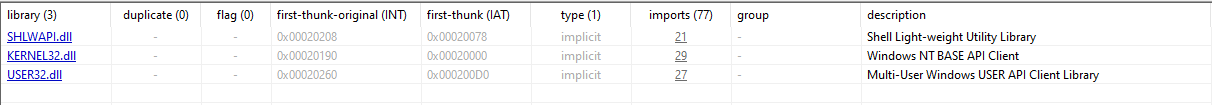

Another interesting section we can look at is the “libraries” section, which provides an overview of the external libraries (DLLs) that the analyzed executable file depends on. It lists the names of these libraries, along with the number of functions imported from each library. Additionally, the section highlights any flagged functions as suspicious based on known malware behaviors which can be followed within the imports tag.

In the above image we have three distinct libraries:

- SHLWAPI.dll (Shell Light-Weigh Utility Library)

- This library contains functions for string manipulation, which in this context, can be leveraged for manipulating paths, files, or registry entries as part of their operation.

- KERNEL32.dll

- This is a core Windows library that contains a wide range of functions that are necessary for any Windows application. In a malware context, it can be used for memory manipulation, process injection, execution control, and interacting with the OS at a low level.

- USER32.dll

- User32 provides functions for creating and managing windows, receiving user input, and handling messages among applications. It can be used maliciously to manipulate windows, capture user input, or create fake dialogs.

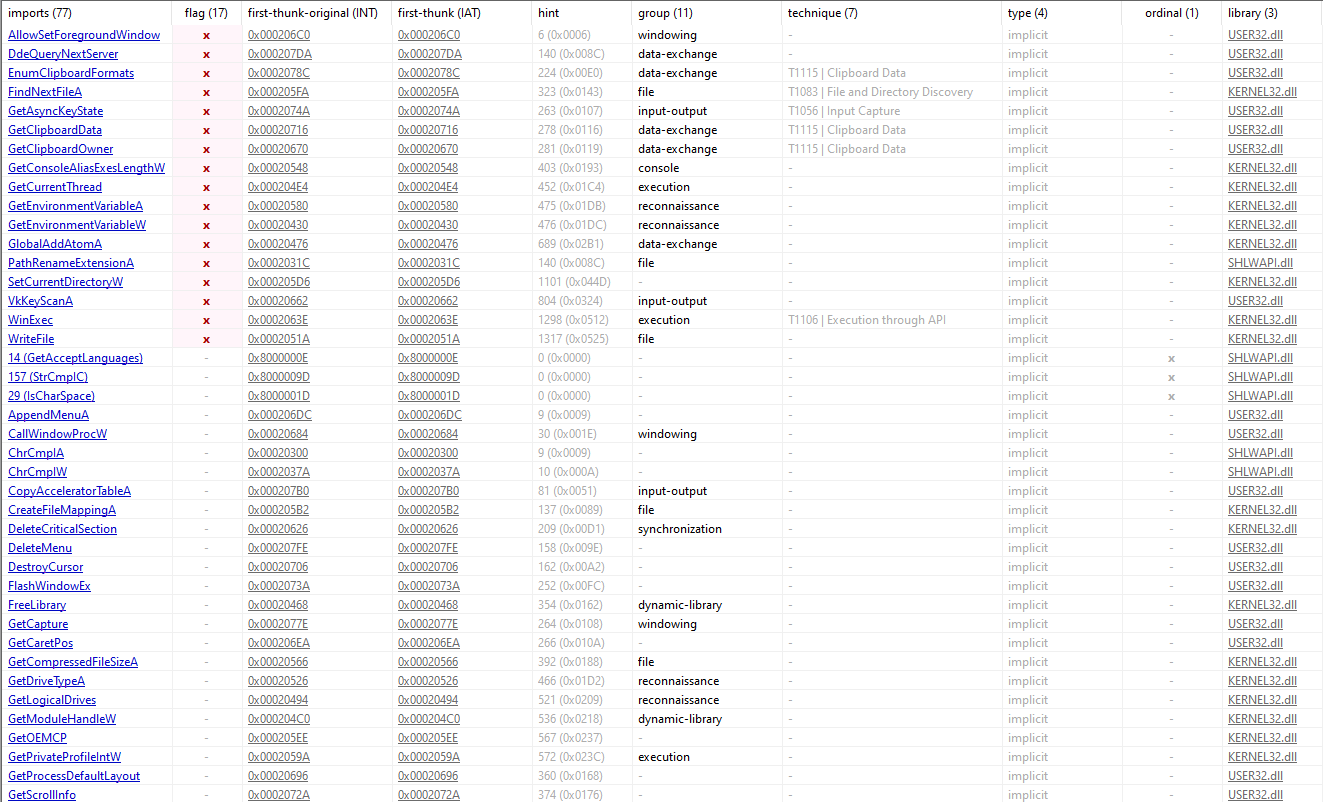

Some interesting fields yield in the imports section can be spotted in the following image:

PathRenameExtensionA can potentially be used to masquerade file types or execute malicious payloads.

WriteFile function is essential for any malware that modifies files or drops new ones.

WinExec executes a program that can directly indicate potential malicious activity if used in certain contexts.

GetClipboardOwner , GetClipboardData , EnumClipboardFormats are functions for interacting with the clipboard, useful for implementing copy-paste funcitionality and determining clipboard content format.

Capa can provide more information on the file, mainly one feature where it will attempt to map to the MITRE ATT&CK framework and other malware catalogues. This globally accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations can assist cybersecurity professionals in understanding and categorizing threats by organizing information about adversary behavior across various stages of an attack. In this instance, we received the following information from Capa:

Given our malware sample, Capa has linked it to the Defense Evasion technique, where it attempts to detect and avoid virtualization and analysis environments. Typically, authors of malware will try to code their software in such a way that it will attempt to detect and avoid virtualization. If the software detects a virtual machine environment, it may disengage and remain dormant, leading to less efficient analysis of the malware.

The MBC Objective field refers to the Malware Behavior Catalog, a collection of documented behaviors exhibited by various types of malwares. These catalogues serve as references for analysts to identify and classify malware based on their observed actions and characteristics, such as Virtual Machine Detection.

The presence of virtual machine detection capabilities in a file suggests that the file is employing evasion techniques to avoid detection and analysis in sandbox environments.

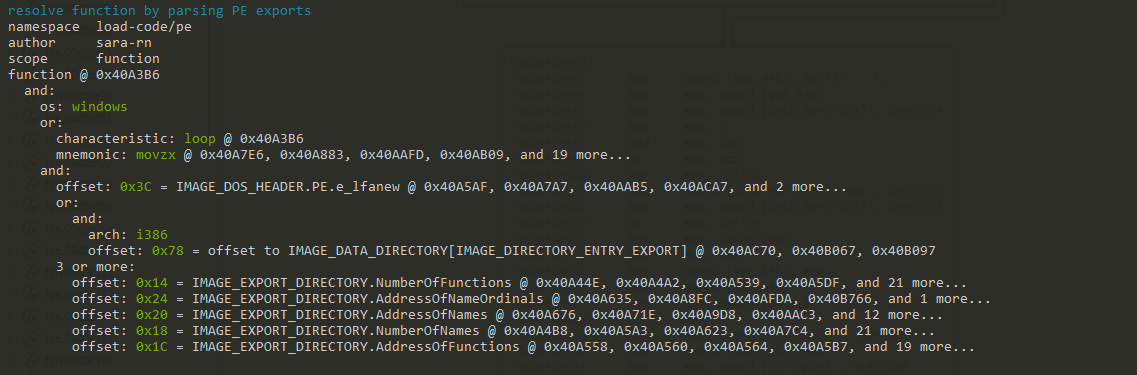

If we pass the Capa command with a very verbose output -vv , we get the various outputs such as:

In here, we can see where exactly in the binary code Capa believes the file to be exhibiting the outlined behavior. Further analysis of the highlighted memory address0x40A3B6 will be continued in our next section.

Advanced Static Analysis

In order to gain greater insight into what this file could potentially do, we can leverage tools such as Ghidra or Cutter to view the disassembled code of files.

When viewing disassembled code, the line labeled as entry indicates the starting point of execution for the program. This is a crucial reference point for analysis and understanding the program flow. This entry label is often associated with a memory address where the corresponding assembly instructions are located within the programs code segment.

It just so happens to be that the flagged memory address 0x40A3B6 is the entry , and therefore, our starting point in the execution of this program.

From here we can make use of the graph function within Cutter to have a greater overview of the entry function. Each rectangular box in the graph represents a basic block of assembly instructions; a sequence of instructions that starts in one specific point and runs sequentially to the last instruction where it may jump to another block based on conditions or proceed to the next block sequentially.

Assembly code when viewed in Cutter tends to be in the following format:

| | Address | Instruction | Operands | Comments | | — | — | — | — | — | | Example | 0x0040a3b6 | push | ebp | ; 0x40fc8c |

- Address: Location in memory where the instruction resides, often represented in hexadecimal format; provides a unique identifier for each instruction’s position in the file.

- Instruction: Assembly language instruction which tells the CPU what operation to perform. Can vary widely, ranging from moving data between registers or memory to controlling the flow of the program.

- Operands: Data items acted upon by the instruction. Can be values, CPU registers, and/or memory addresses. Multiple operands are possible.

- Comments: Semicolon starts a comment in assembly language. These are not part of the machine code but are added to provide explanations.

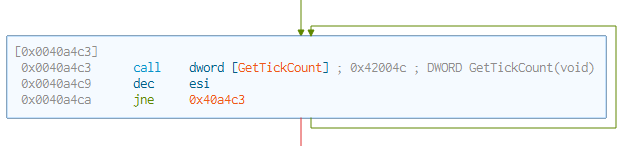

Within the entry function we find the following interesting instruction:

0x0040a4c3 could potentially be the reason why Capa flagged the corresponding function as suspicious Defense Evasion. In the fifth block of assembly instructions, we find the operand [GetTickCount] which can be used to retrieve the number of milliseconds that have elapsed since the system was started. Although this API function is not inherently malicious it has been shown to be used for time based evasion. Sandboxes often have time limitations on how long a program can run or how many operations it can perform within a certain timeframe. By using GetTickCount to measure time intervals, malware can delay the execution of malicious behavior until after the sandbox environment has achieved specific victim conditions.

In this specific instance we see a call instruction to the GetTickCount, retrieving a value in milliseconds and storing it in a register for future use. Then, a decrease instruction of one is passed on a value found within the ESI register (a register typically used as a loop counter). Then, a check is passed to see if the ESI value is not equal to zero. If the value is zero, then it jumps to the following block of code instruction, but if the value is not zero, then a loop is started until the condition is met.

By repeatedly checking the system’s uptime or elapsed time using the GetTickCount, malware can delay its malicious behavior until a certain condition is met.

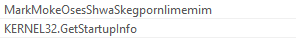

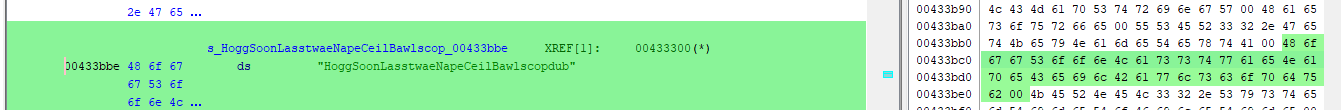

Following up on the possible obfuscation techniques alluded to in the PEstudio strings section can be done by analyzing the random strings and functions with their corresponding memory addresses.

Take for example the following string and function:

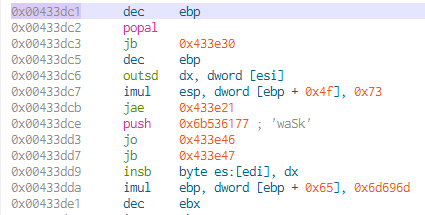

When performing a string search for MarkMokeOsesShwaSkegpornlimemim we are taken to a memory address 0x00433dc1

When performing a search for function KERNEL32.GetStartupInfo we are taken to memory address 0x00433de1

Note the proximity in memory address of the two:

Here we can notice the close the string and function are within the disassembled code, indicating a relationship between the two. The juxtaposition of random strings with system function calls could demonstrate an attempt at obfuscation or could be part of a more complex mechanism like a custom encryption/decryption routing that uses these strings.

Another interesting point can be found between these two memory addresses:

One instruction has the reference of ‘waSk’ which is a small portion of the before mentioned string. This pattern can be seen again with the use of seemingly random strings and a function call.

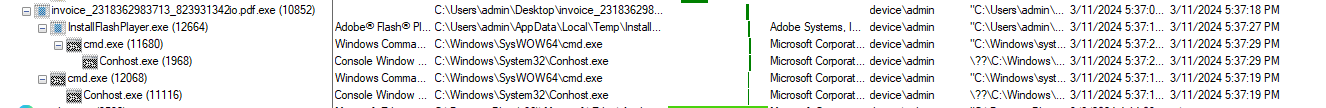

- String:

AsksmaceaglyBubuPulsKaifTeasMistPeelGhisPrimChaoLyreroeno- Memory Address:

0x004337a

- Memory Address:

- Function:

KERNEL32.MulDiv- Memory Address:

0x004337dc

- Memory Address:

- String portion:

isPr- Memory Address:

0x004337c7

- Memory Address:

.png)

Note: I had to add in the corresponding function address. Cutter would automatically hide it once any movement would be made.

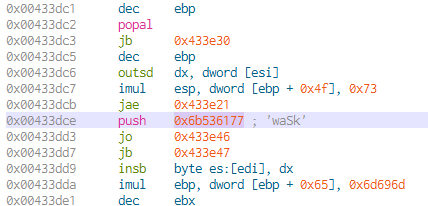

- String:

CellrotoCrudUntohighCols- Memory Address:

0x0043396c

- Memory Address:

- Function:

KERNEL32.CreateFile- Memory Address:

0x00433985

- Memory Address:

- String portion:

ighC- Memory Address:

0x0043397c

- Memory Address:

While static analysis serves as a foundational step in understanding the characteristics of the analyzed malware sample, it is essential to complement this with dynamic and behavioral analysis techniques to gain insights into its actual behavior and impact on a system. Furthermore, the application of YARA-based classification methods adds another layer of analysis, allowing for the identification of known malware patterns or signatures, and integrating hybrid analysis platforms will provide additional context and validation, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the analyzed sample.

Dynamic Analysis

In this section, we explore dynamic analysis, a crucial step in malware analysis involving the execution of malware in a controlled environment to observe its behavior in real-time. Unlike static analysis, which focuses on file properties, dynamic analysis allows us to directly monitor the malware’s actions, including file modifications, network communications, and system interactions. Through techniques such as process and behavior monitoring, we aim to uncover the malware’s capabilities, intentions, and potential impact.

Procmon, short for Process Monitor, is a powerful Windows utility developed by Microsoft for monitoring system activity in real-time. By capturing events related to process and thread activity, file system and registry operations, and network communications, Procmon provides detailed insights into the behavior of running applications and processes. We can leverage Procmon to track malware’s actions such as file creations, registry modifications, and network connections, enabling us to identify malicious behaviors and understand the malware’s impact on the compromised system. Additionally, with its filtering and logging capabilities, Procmon streamlines the analysis process by allowing users to focus on relevant events and quickly pinpoint suspicious activity, facilitating effective dynamic analysis workflows.

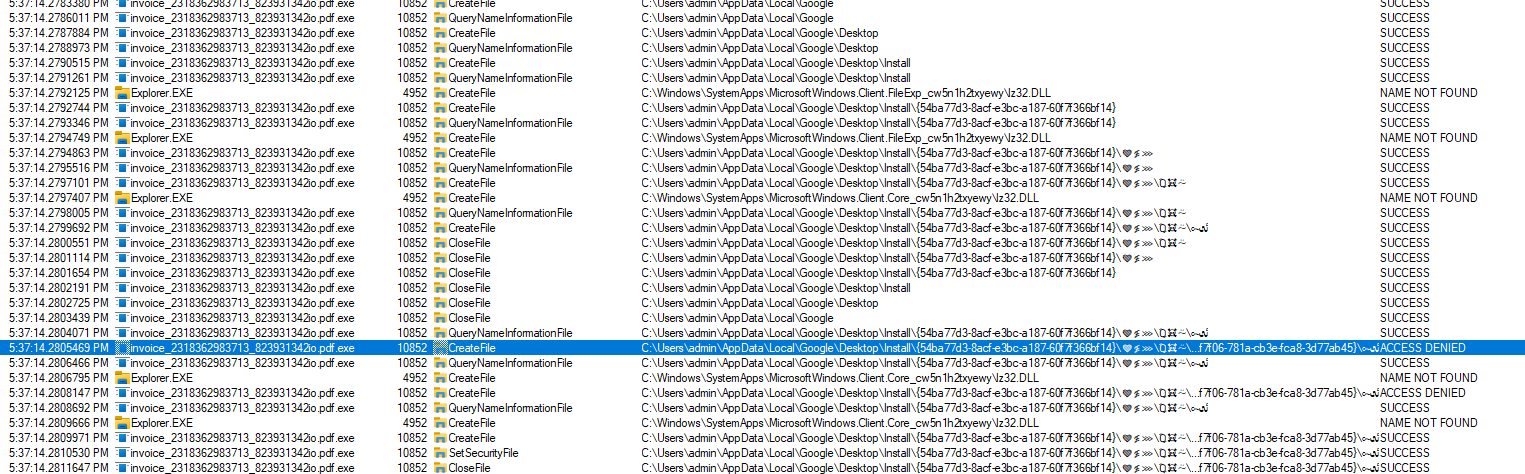

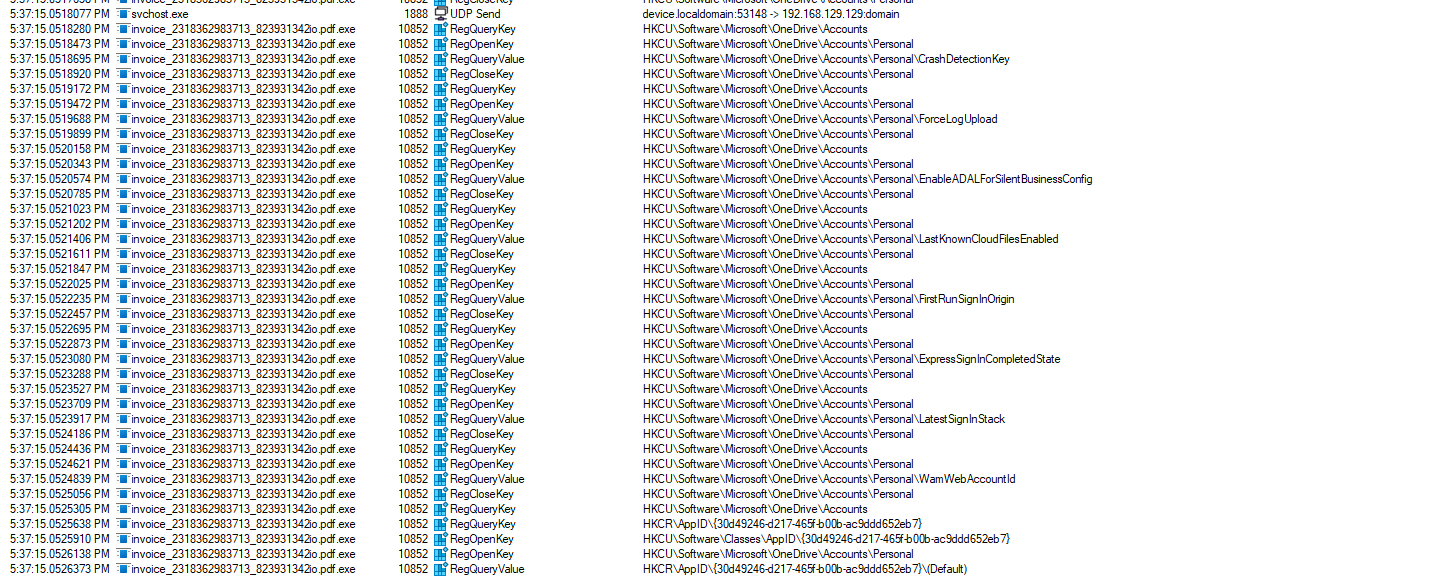

The analyzed malware sample, labeled as invoice_2318362983713_823931342io.pdf.exe, presents itself as a PDF file but is in fact an executable that can be triggered merely by execution. Leveraging Procmon’s monitoring capabilities, we embark on a journey to unravel the intricacies of this deceptive file’s behavior. Through meticulous event capturing and analysis, Procmon serves as our lens into the inner workings of malware, offering valuable insights into its activities and intentions.

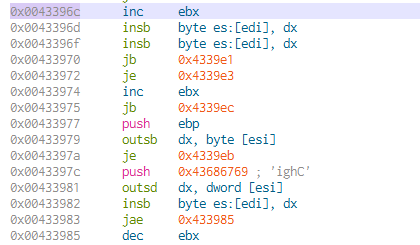

First, we can make use of the process tree utility within Procmon to note suspicious processes that may have been executed by the file:

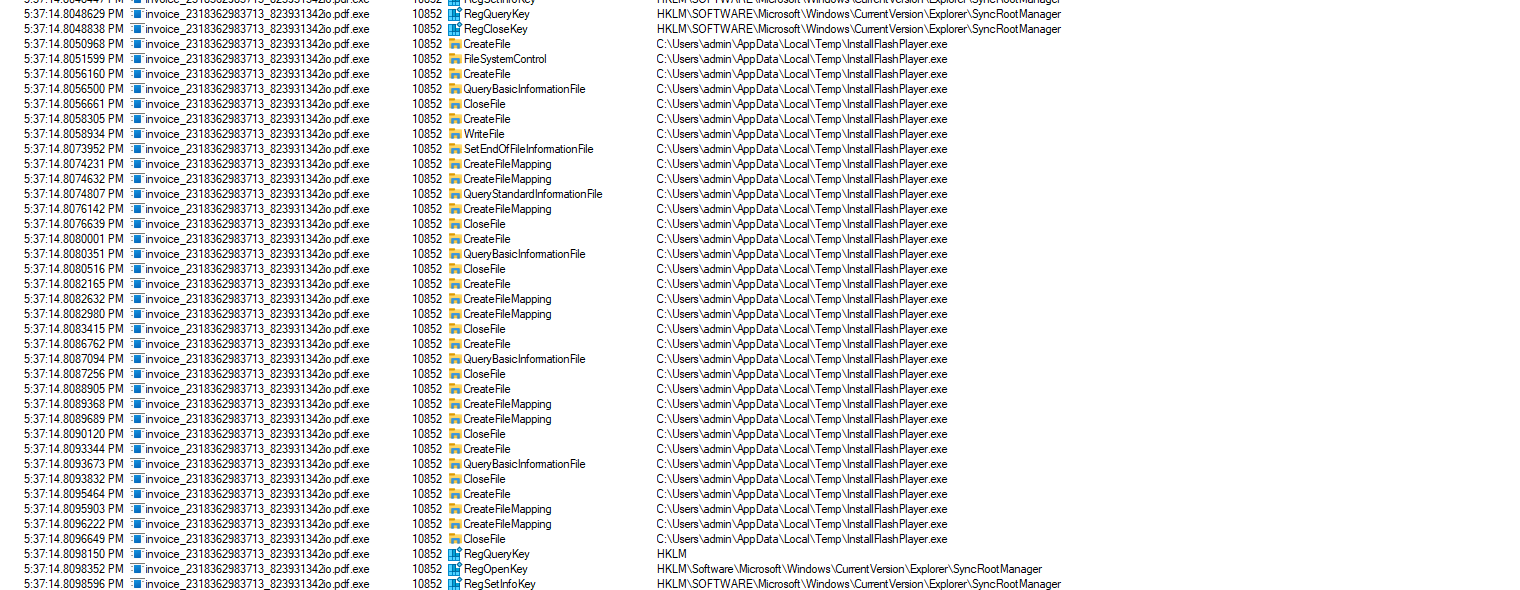

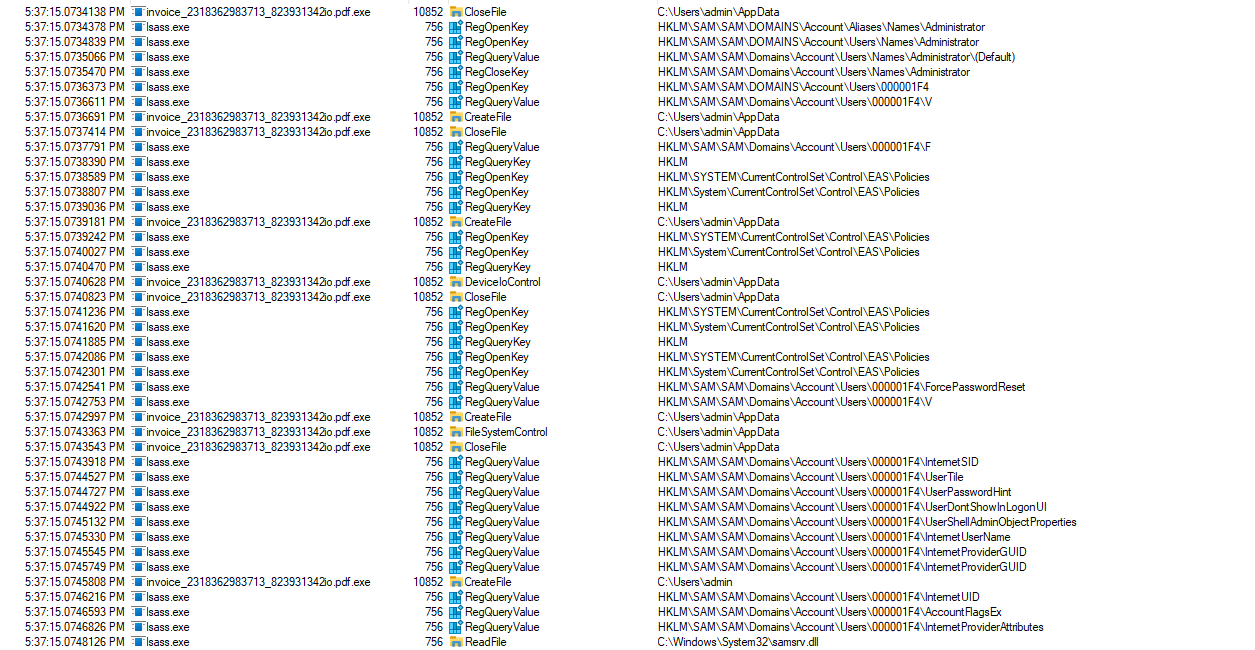

At the top of this process tree looms the invoice file itself, spawning a cluster of associated processes, notably InstallFlashPlayer.exe, cmd.exe, and conhost.exe . The emergence of these processes, particularly in conjunction with the suspicious nature of the invoice file, prompts further investigation into additional processes exhibiting similar behavioral patterns.

Following the processes that involve the invoice file, we start to note suspicious actions that are typically not associated with a pdf file, such as the CreateFile operation.

Not only is the operation itself indicative of malicious behavior, but the directory in which the file is created also raises significant red flags: C:\Users\admin\AppData\Local\Google\Desktop\Install\{54ba77d3-8acf-e3bc-a187-60f7f366bf14}\❤≸⋙\Ⱒ☠⍨\ﯹ๛\{54ba77d3-8acf-e3bc-a187-60f7f366bf14}

The inclusion of Unicode characters and symbols in the directory path suggests an attempt to obfuscate the true nature of the installation directory. Such obfuscation techniques are frequently employed by malware to conceal their presence on the system and evade detection by security measures.

Similarly, malicious files often find refuge in the AppData directory due to its permissive nature, allowing executables and data to be stored without necessitating administrative privileges. By exploiting this accessibility, malware can circumvent security measures that restrict access to system directories and potentially evade User Account Control prompts.

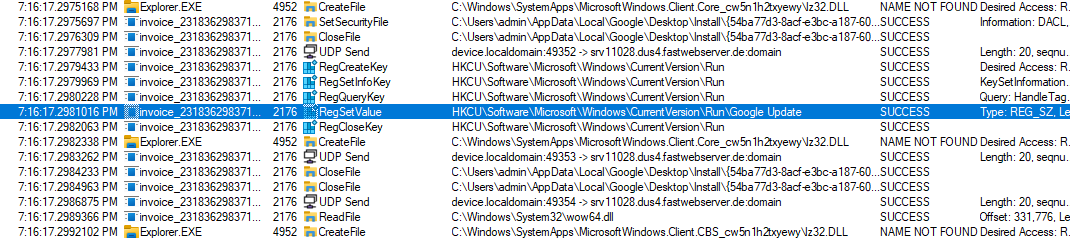

The image below provides evidence of this persistence mechanism, where the infamous invoice file changes a value within the Windows Registry.

The Windows registry is a vital database storing system and application configurations. Any alterations to its values can impact system stability and security. Thus, it’s suspicious when a file, particularly one with potential malicious intent, attempts to modify registry entries. Malware often seeks to establish persistence by adding entries to specific registry keys, such as those within the \Run directory. By doing so, the malware ensures that it is executed automatically whenever the system boots up or a user logs in. This tactic allows the malware to maintain a foothold on the compromised system, enabling continuous operation and potential further compromise.

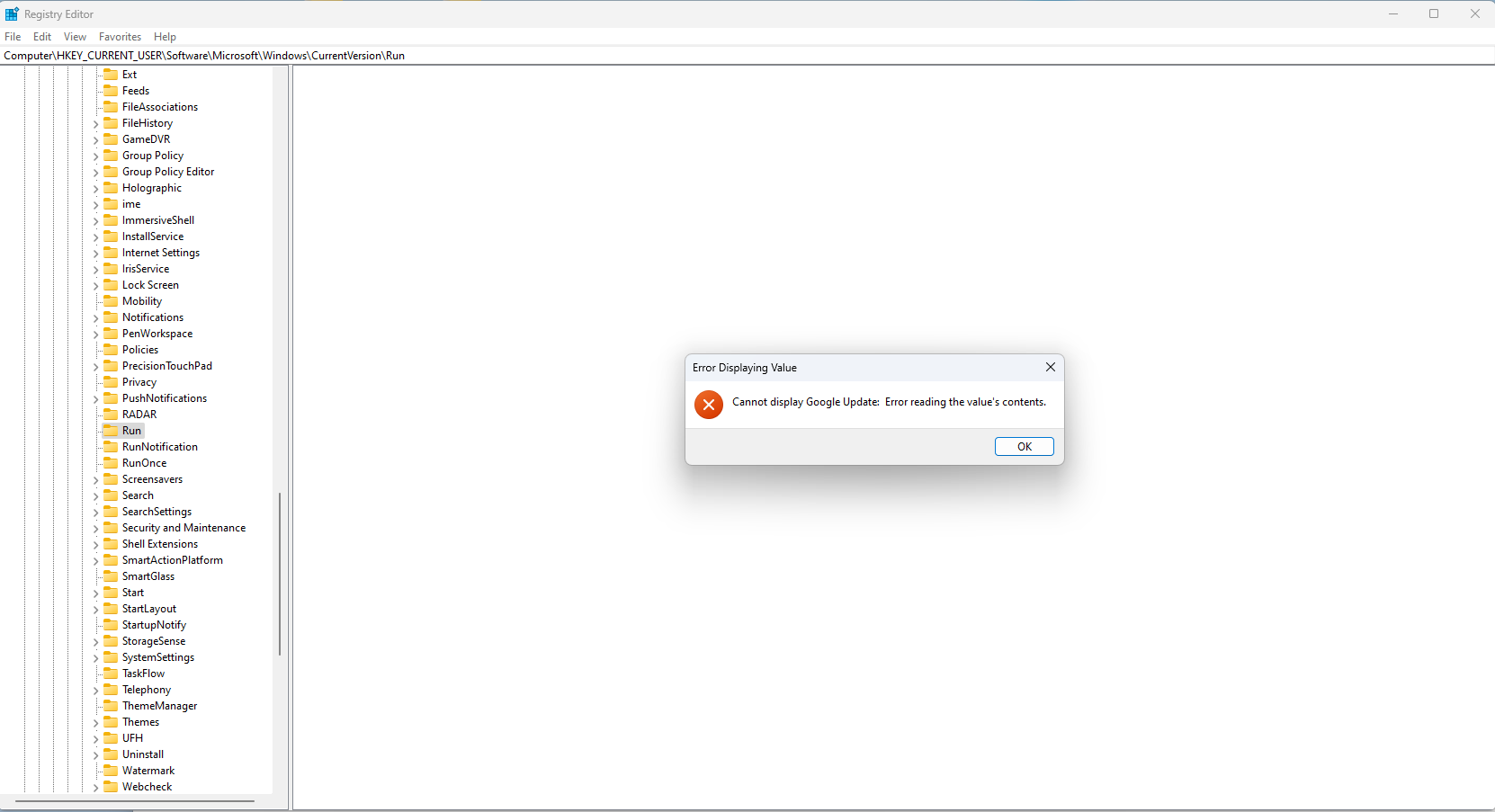

One cool feature Procmon has is the “Jump To” feature, which allows us to swiftly navigate to this value in the Registry Editor for detailed examination. However, the following message appears:

The occurence of an error message when attempting to access specific registry values, such as the one shown above, raises suspicions during malware analysis. The error suggests potential tampering or corruption of registry entries by the malware, hindering visibility into its activities and potentially indicating attempts to evade detection or manipulate system settings clandestinely.

Persistance, by definition, entails the ongoing effort to maintain a foothold within a system. Consequently, establishing multiple points of persistence can enhance a malware’s ability to evade detection and sustain its activities over time. This strategy is exemplified by the installation of InstallFlashPlayer.exe :

The malware’s tactics appear to evolve to a more direct approach in gathering data from the victim’s device, as evidenced by its attempts to access OneDrive accounts:

This indicates a shift towards targeted data exfiltration, potentially involving the theft of sensitive information stored in cloud-based repositories. Such actions demonstrate the malware’s intent to exploit various avenues for data acquisition, underscoring the severity of its impact on the victim’s privacy and security.

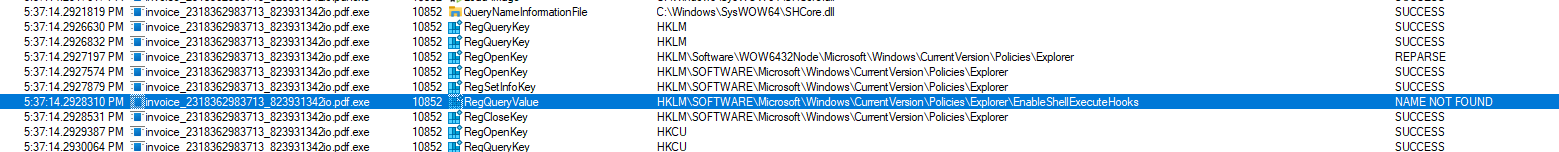

Furthermore, there is an attempt to query the Windows registry for EnableShellExecuteHooks :

ShellExecuteHooks are mechanisms that allow applications to monitor and intercept actions performed through the ShellExecute function. By hooking into this process, a malicious program could monitor and potentially manipulate the execution of applications or files on the system. Similarly, it could allow the malware to monitor actions such as file executions, which can in turn be used for purposes like logging user activities, intercepting sensitive data, or launching additional payloads.

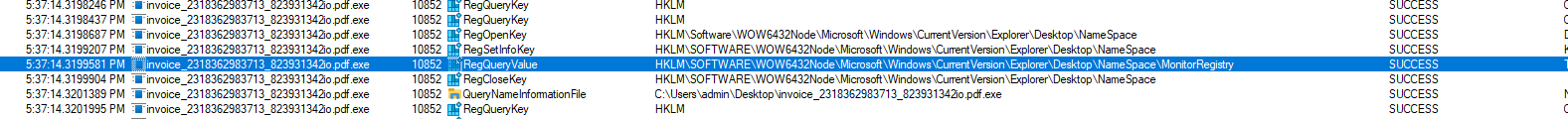

Take as an example the following registry query:

The malicious invoice process now extends its reach by searching for a registry key associated with monitoring registry changes, indicating an intent to gain deeper insight into user activities, system modifications, or security mechanisms. However, the intrusion does not stop there; the process proceeds to probe the registry for information pertaining to SAM (Security Accounts Manager):

SAM is a crucial component of the Windows operating system responsible for storing user account information, including passwords and security policies. It serves as the primary database for user authentication, facilitating access control and security enforcement within the system. Access to SAM data is highly restricted, and unauthorized manipulation can lead to serious security breaches and compromise of sensitive information.

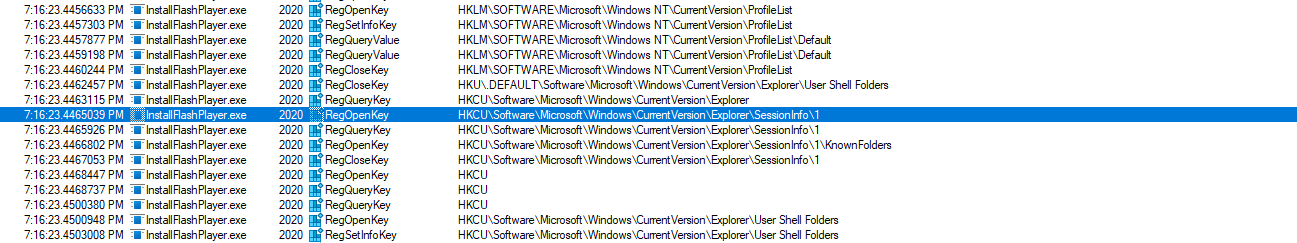

The invoice process proceeds to utilize another process it spawned, InstallFlashPlayer.exe to conduct further reconnaissance and data collection. This symbiotic relationship allows the malware to extend its reach and gather additional intelligence about the compromised system:

Performing queries into registry keys related to SessionInfo and KnownFolders can be problematic, as these typically contain session information, indicating an attempt to gather sensitive data about user sessions, active processes, or system activities.

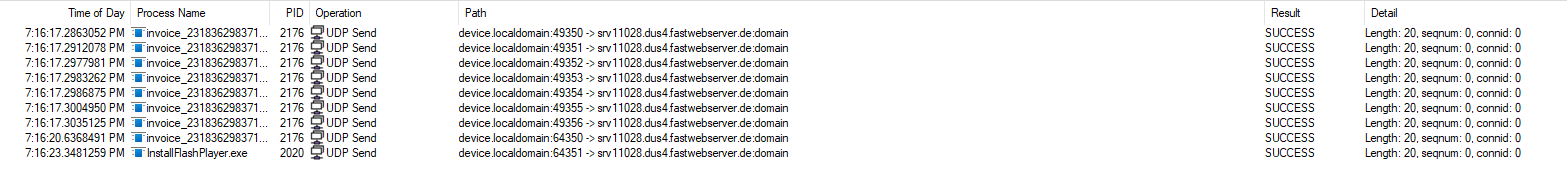

As the malware’s infiltration advances, it undergoes a crucial shift: transitioning from internal data collection to the transmission of gathered information to an external host. This pivotal change underlines the malware’s readiness to exfiltrate sensitive data or establish communication with remote servers, significantly heightening the threat it poses to both individual privacy and overall system security.

Malware often resorts to DNS (Domain Name System) for data exfiltration due to its ubiquitous presence and inherent characteristics. DNS traffic is typically allowed through firewalls and other security measures, making it an attractive choice for stealthy communication. By encoding data within DNS queries or responses, malware can bypass network detection systems and evade scrutiny. Additionally, DNS offers a convenient means of communication with remote servers, enabling malware to transmit sensitive information discreetly while maintaining a low profile on the compromised system.

In this instance, we see both the invoice and flash process reach out to a certain domain:

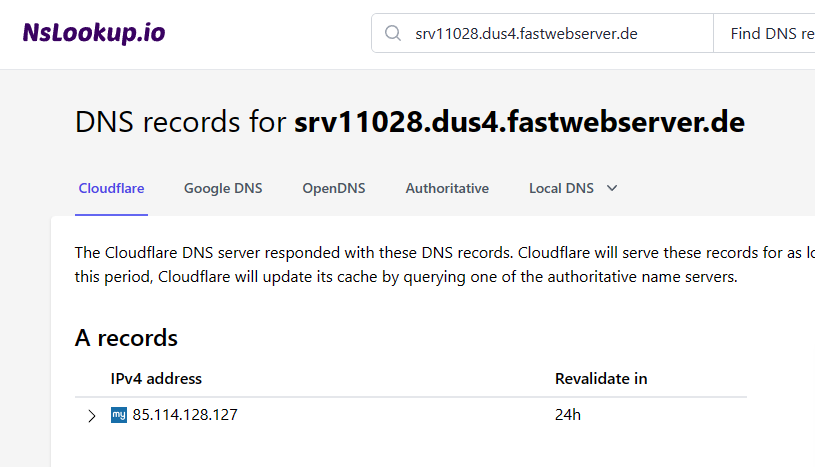

When we perform some DNS queries on this domain, we get the following information:

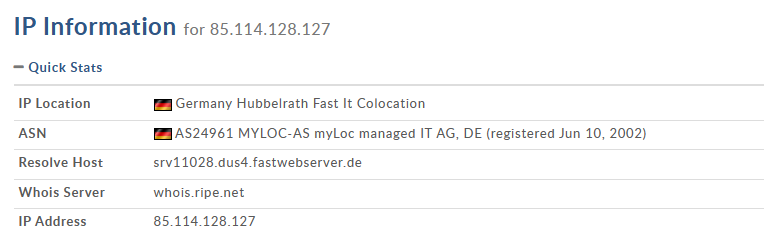

Further investigating domain name registration information shows the potential host, located in Germany:

Multiple DNS connections to a host in Germany, given our designated United States IP location for our virtual machines, without any clear business or operational justification, significantly raise security concerns. Such unusual network activity, especially when directed towards a foreign entity with no apparent relation to the victim’s normal operations, suggests potential malicious communication. This pattern is a red flag for cybersecurity analysts, indicating possible data exfiltration or command-and-control interactions, and warrants immediate investigation to mitigate threats and secure the compromised system.

With the suspicion of malicious DNS activity pointing towards unauthorized data exchanges, the next logical step involves deepening our investigation through packet analysis. Utilizing Wireshark, a powerful network protocol analyzer, allows to capture and examine the specifics of network traffic, including these questionable DNS connections. This transition into packet analysis with Wireshark will enable us to dissect the data packets in detail, providing invaluable insights into the nature of the malware’s communication and further clarifying the scope of the threat.

The Wireshark interface is designed to provide comprehensive visibility into network traffic with its user-friendly layout. The main section of the interface displays captured networks packets in a customizable packet list, showing details such as source and destination addresses, protocols, and packet lengths. More information can be displayed in the packet details pane, offering in-depth information about the selected packet. Additionally, Wireshark features a powerful packet filter and search functionality, allowing users to precisely analyze specific packets or network traffic patterns.

The Wireshark interface is highly customizable, but for this project we will use the following columns:

| Packet Number | Time | Source IP | Destination IP | Protocol | Packet Length | Information | | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

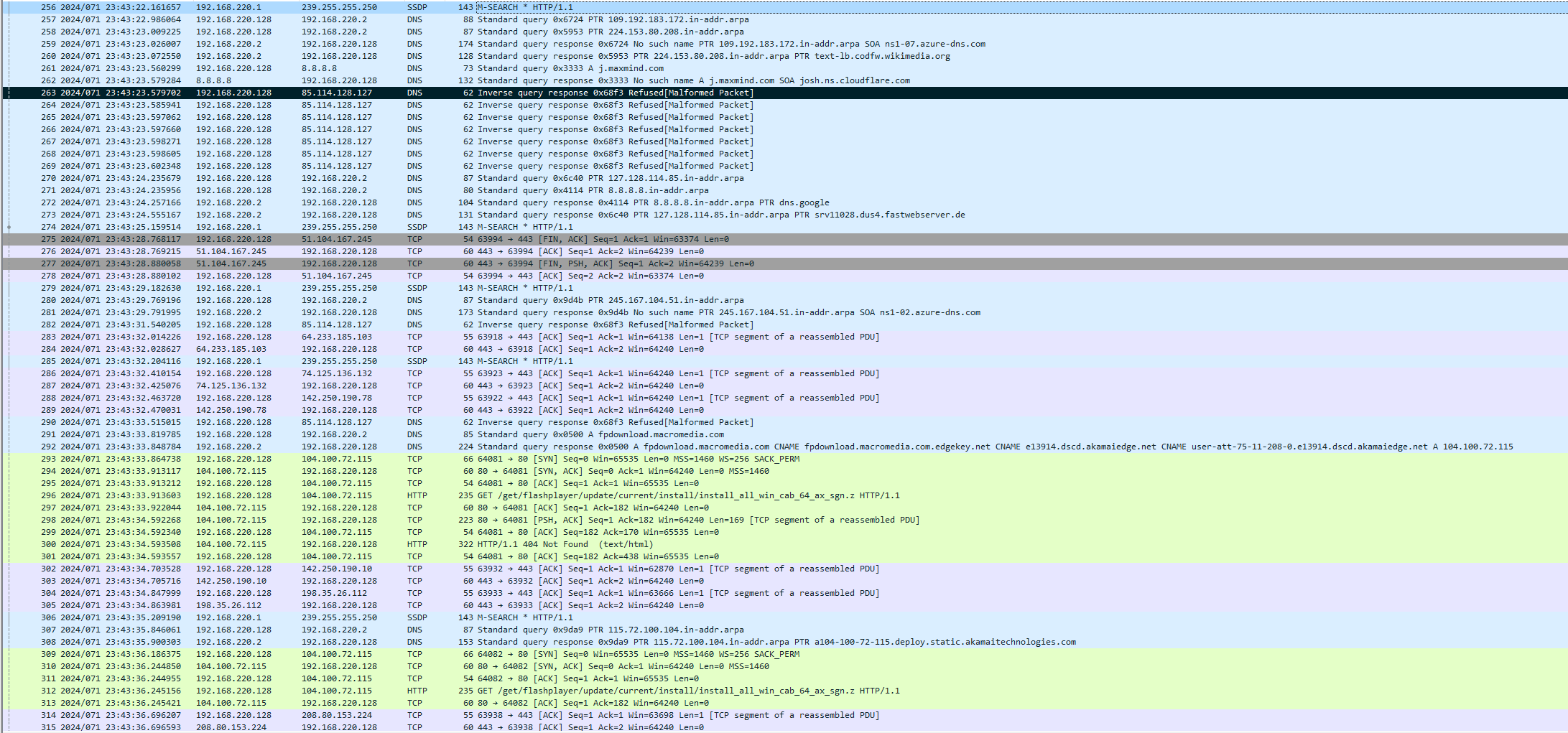

The following image shows us the most noteworthy packets that occur after malware detonation:

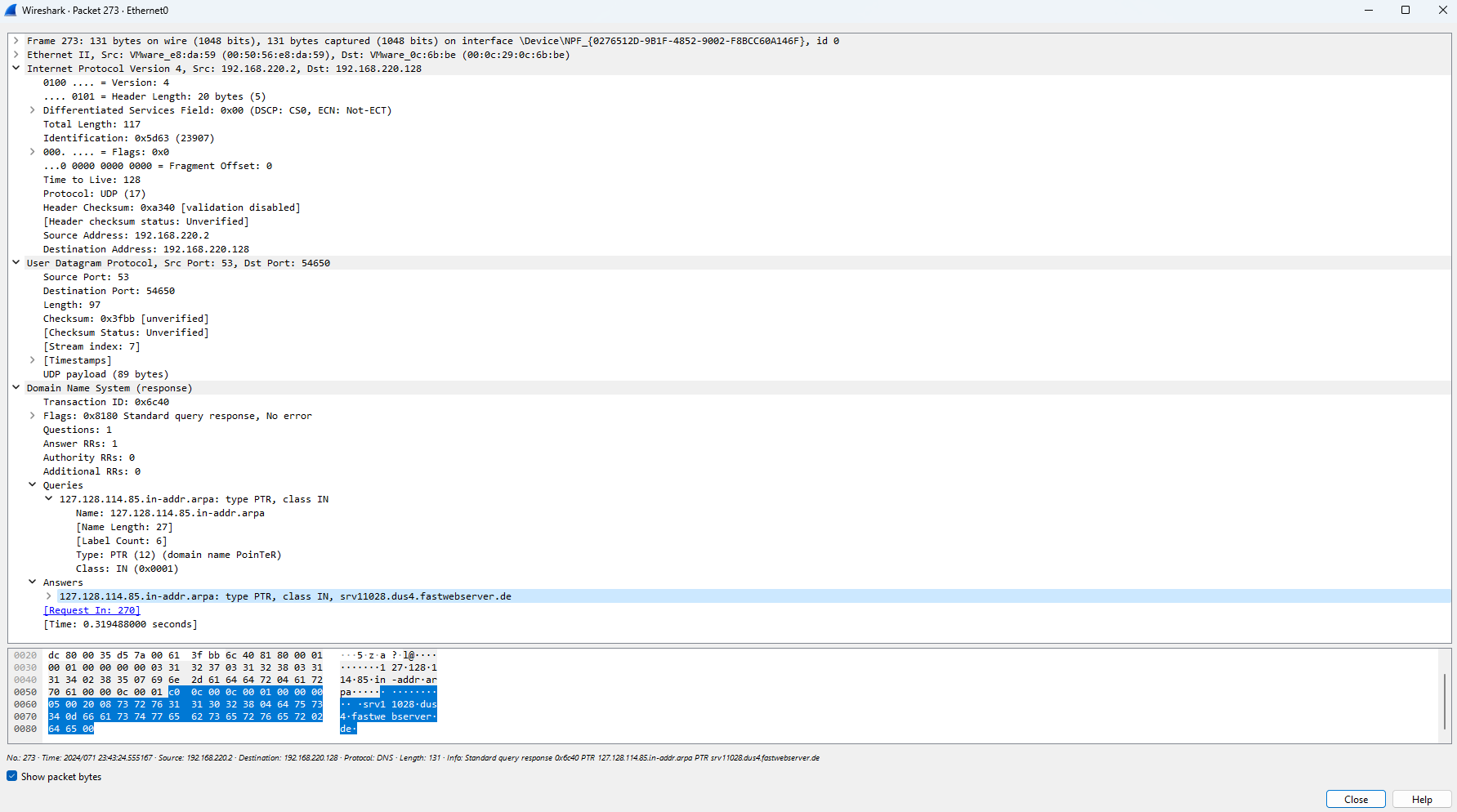

In packet 256-260, we see an attempt to leverage reverse DNS lookups as a covert means to determine the IP address of a victim, note the use of “in-addr.arpa”:

By querying DNS servers with the victim’s IP address, the malware can retrieve associated domain names, potentially revealing valuable information about the victim’s network infrastructure or geographic location. This tactic provides malicious actors with crucial intelligence for orchestrating targeted attacks or further exploiting vulnerable systems. Additionally, reverse DNS lookups offer a stealthy method of reconnaissance, as they may go unnoticed amidst legitimate network traffic. In these packets, the relevance of “in-addr.arpa” lies in its usage as the domain reserved for reverse DNS lookups, facilitating the translation of IP address back to domain names

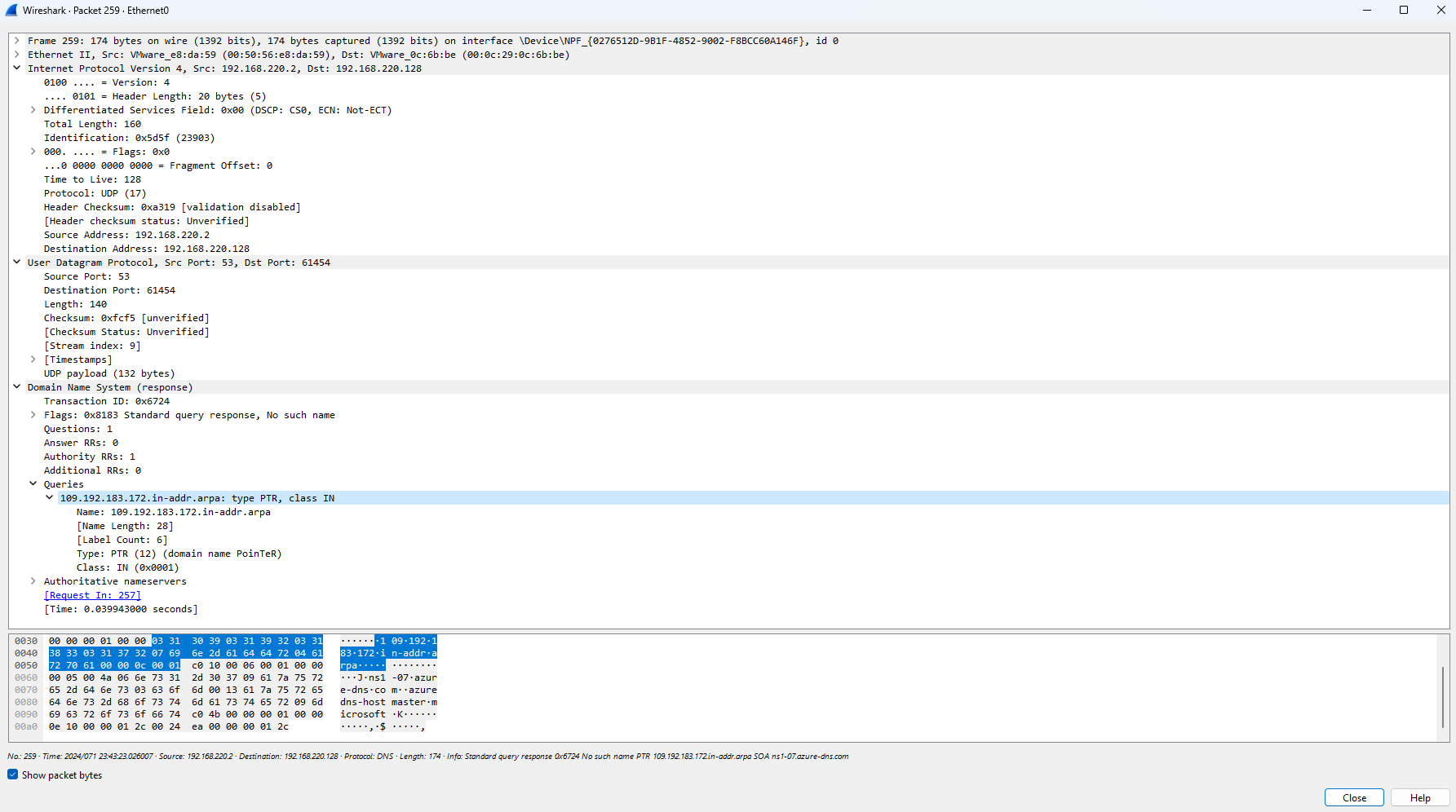

Next, we use a DNS query into ‘j.maxmind.com’ in packets 261-262:

The presence of a query to MaxMind in the network traffic suggests a potential attempt by the malware to utilize its geolocation capabilities. MaxMind offers an extensive geolocation database and API services, allowing applications to determine the geographical location associated with an IP address. In this context, the malware may be seeking to gather location-based information about the victim’s IP address, enabling the threat actor to tailor their attack or gather intelligence about the target’s geographic location. The utilization of MaxMind’s services underscores the malware’s sophistication and its intent to gather precise information for nefarious purposes.

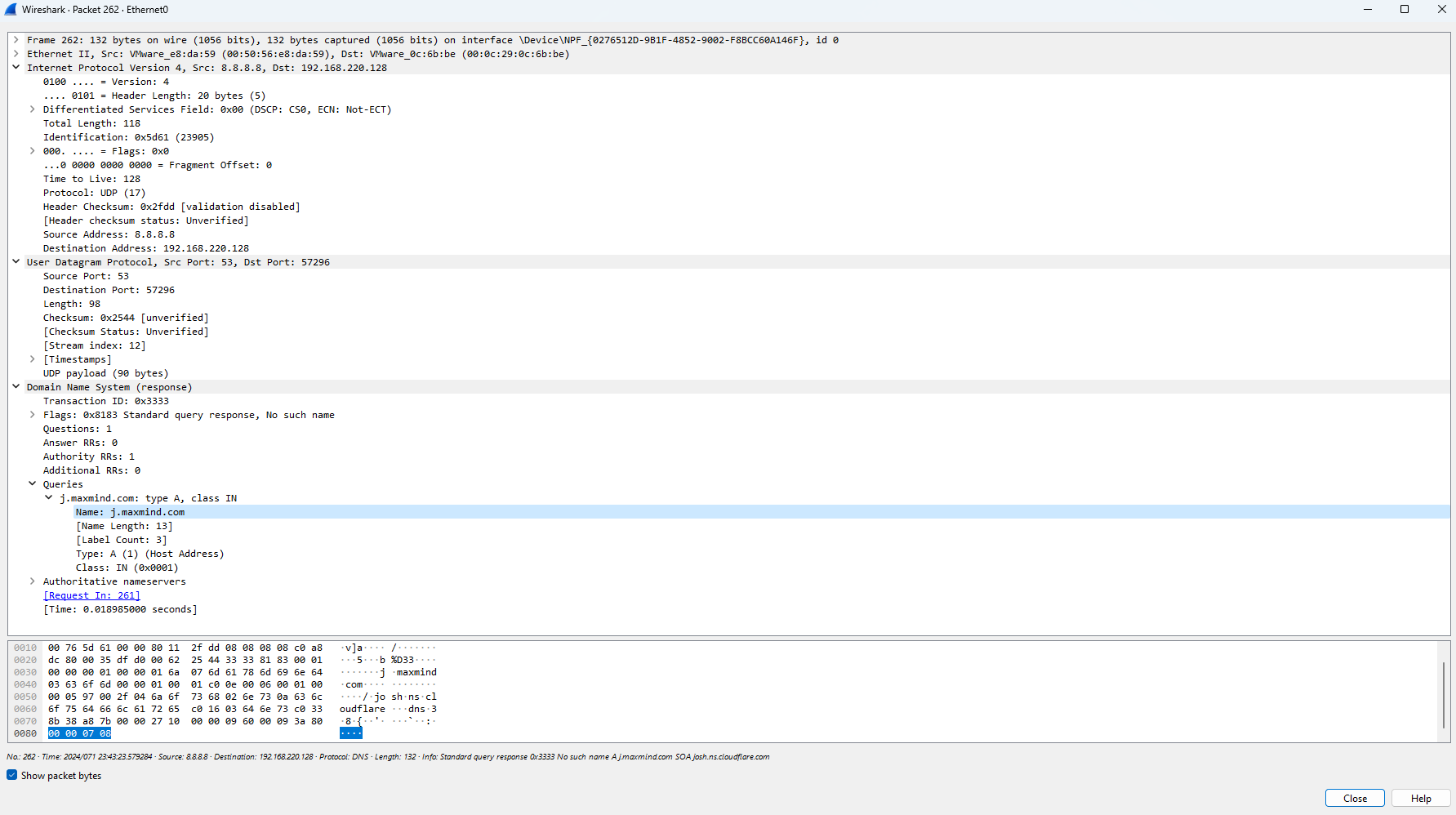

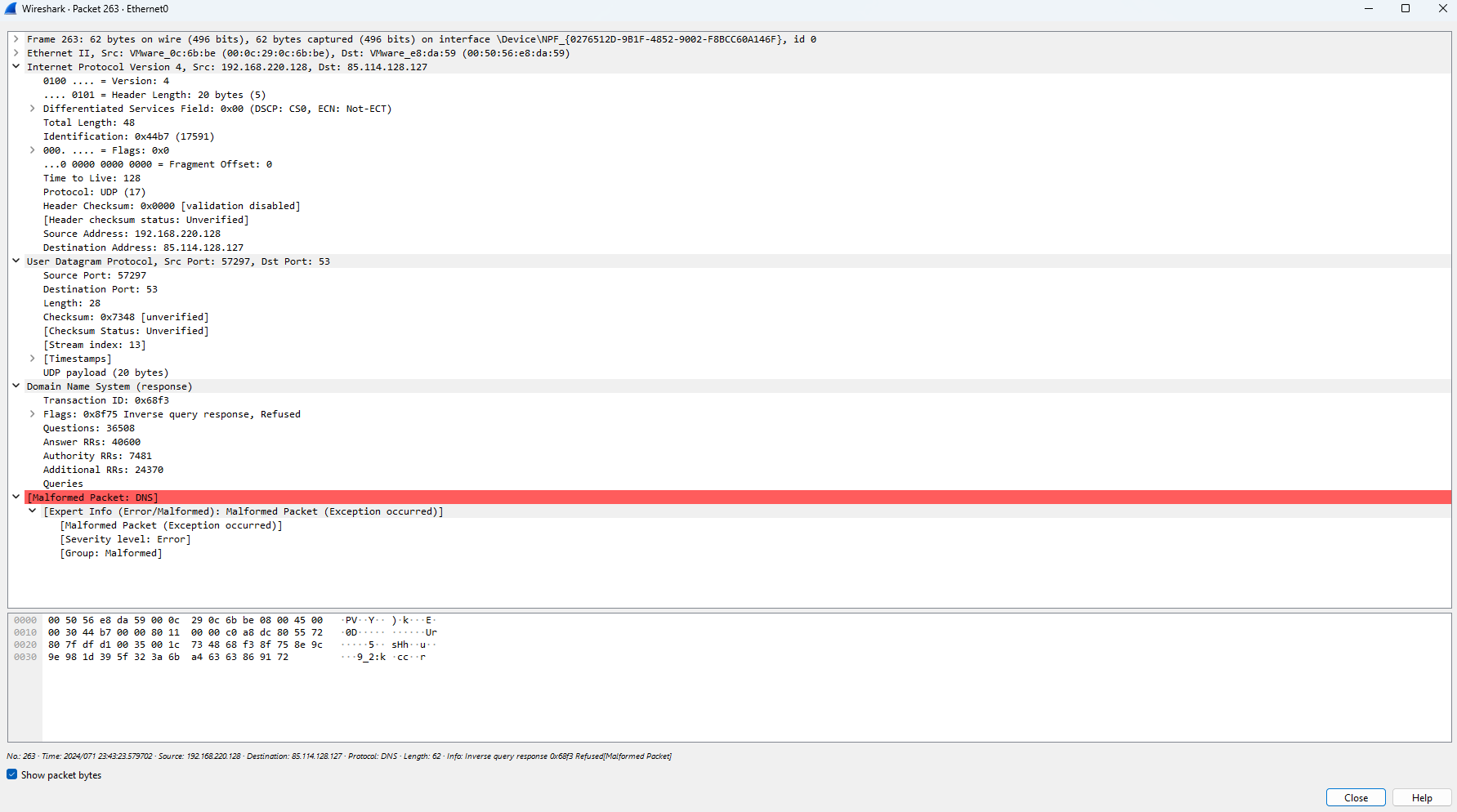

Packets 263-269 shows the before mentioned suspicious German IP address being reached out to numerous times:

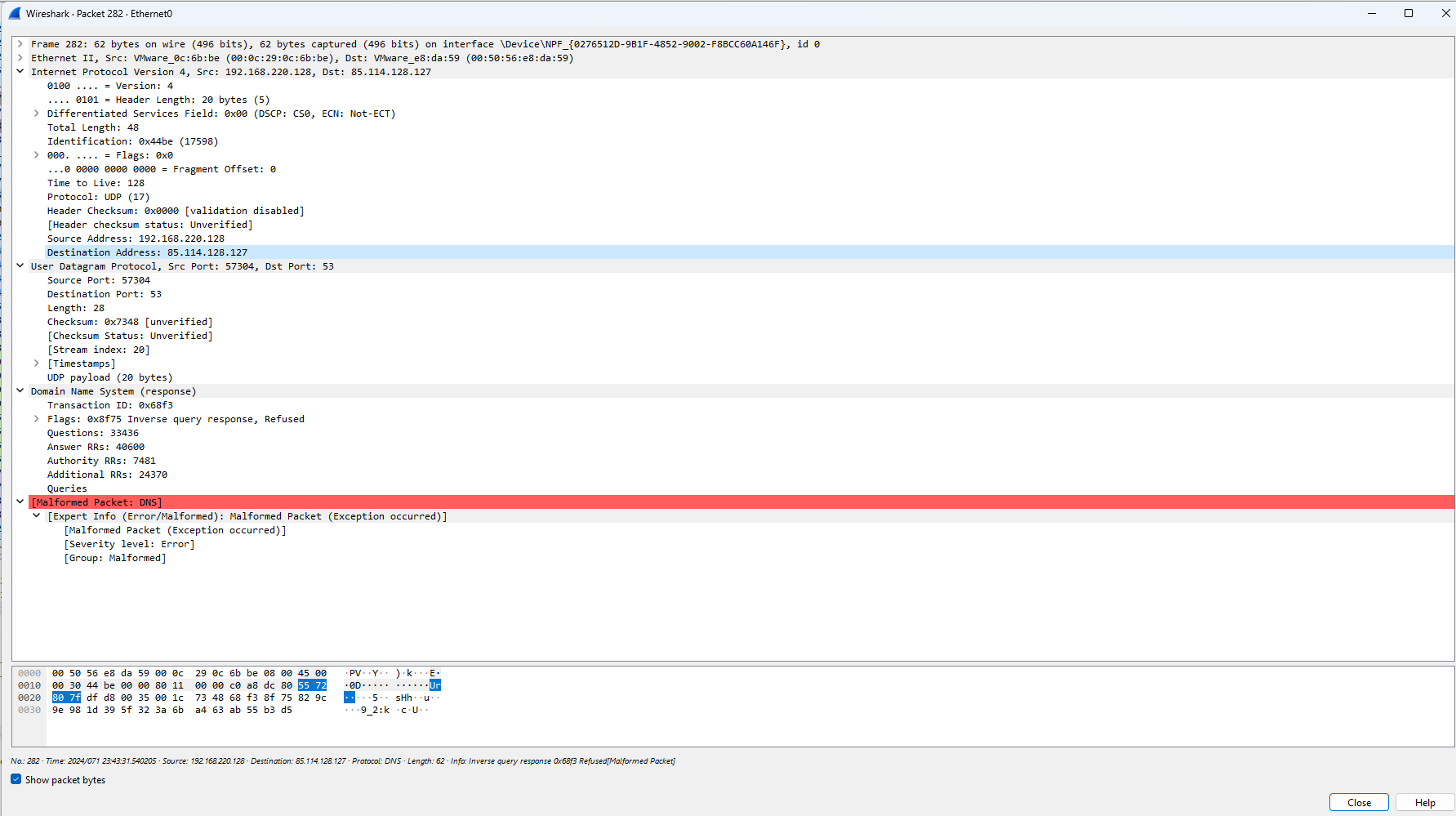

The presence of numerous packets directed towards the suspicious German IP address raises significant concerns, particularly when coupled with indications that inverse query responses have been refused. Such behavior is highly suspicious, as it suggests an attempt by the malware to establish communication with a potentially malicious host while actively avoiding scrutiny or identification through inverse DNS queries. This refusal to provide reverse DNS information heightens the likelihood of malicious intent, underscoring the urgency of further investigation to mitigate potential threats and protect the integrity of the network.

Furthermore, we see more reverse dns lookups performed to a domain that is linked to the German IP address in packet 273:

A few packets later in 282 and 290 we see the potential host, 85.114.128.127, being reached out to again, and the same inverse query response is refused:

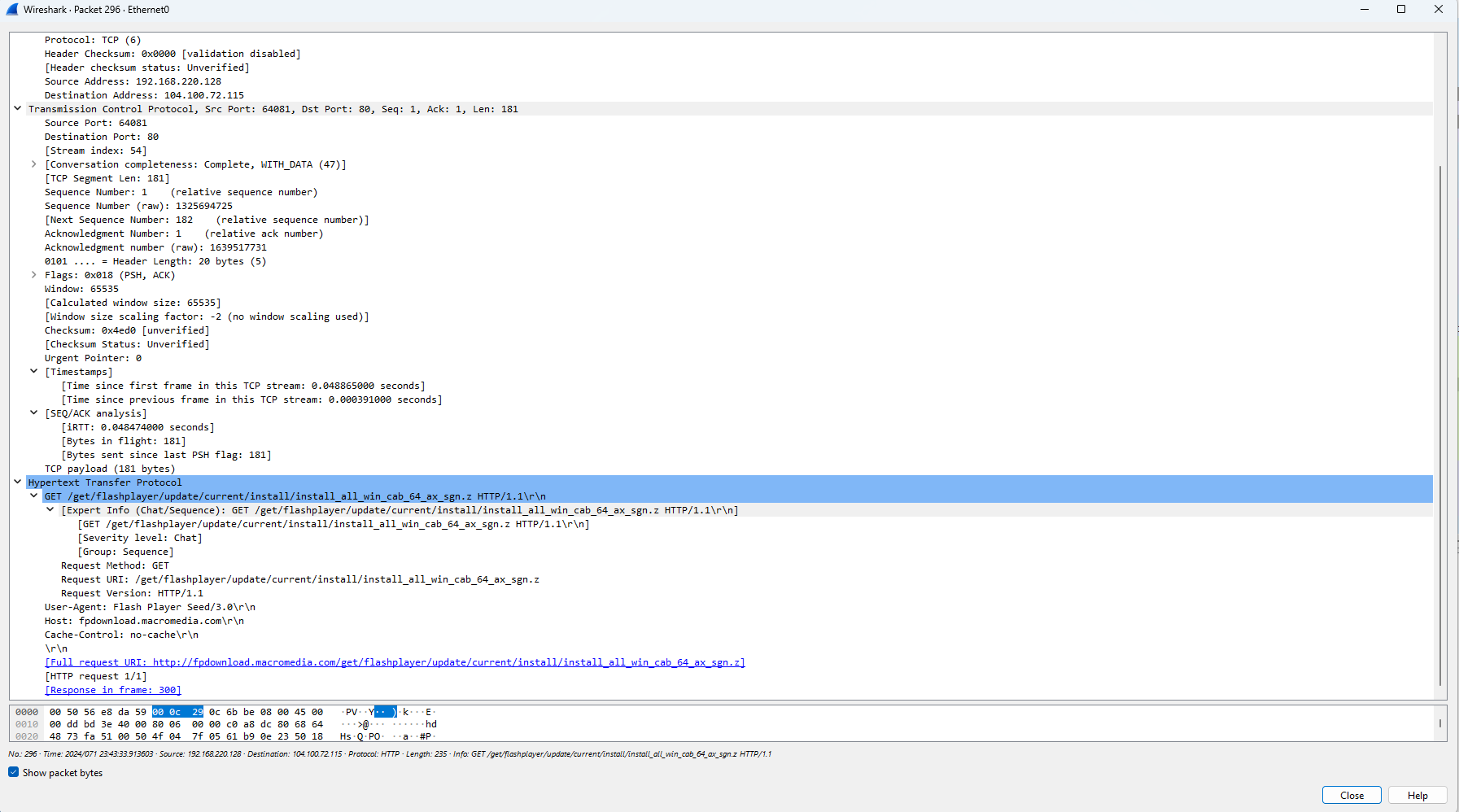

Finally, we see in packets 291-296, a domain resolution is undertaken, and results in a HTTP Get request that downloads a flash player installer:

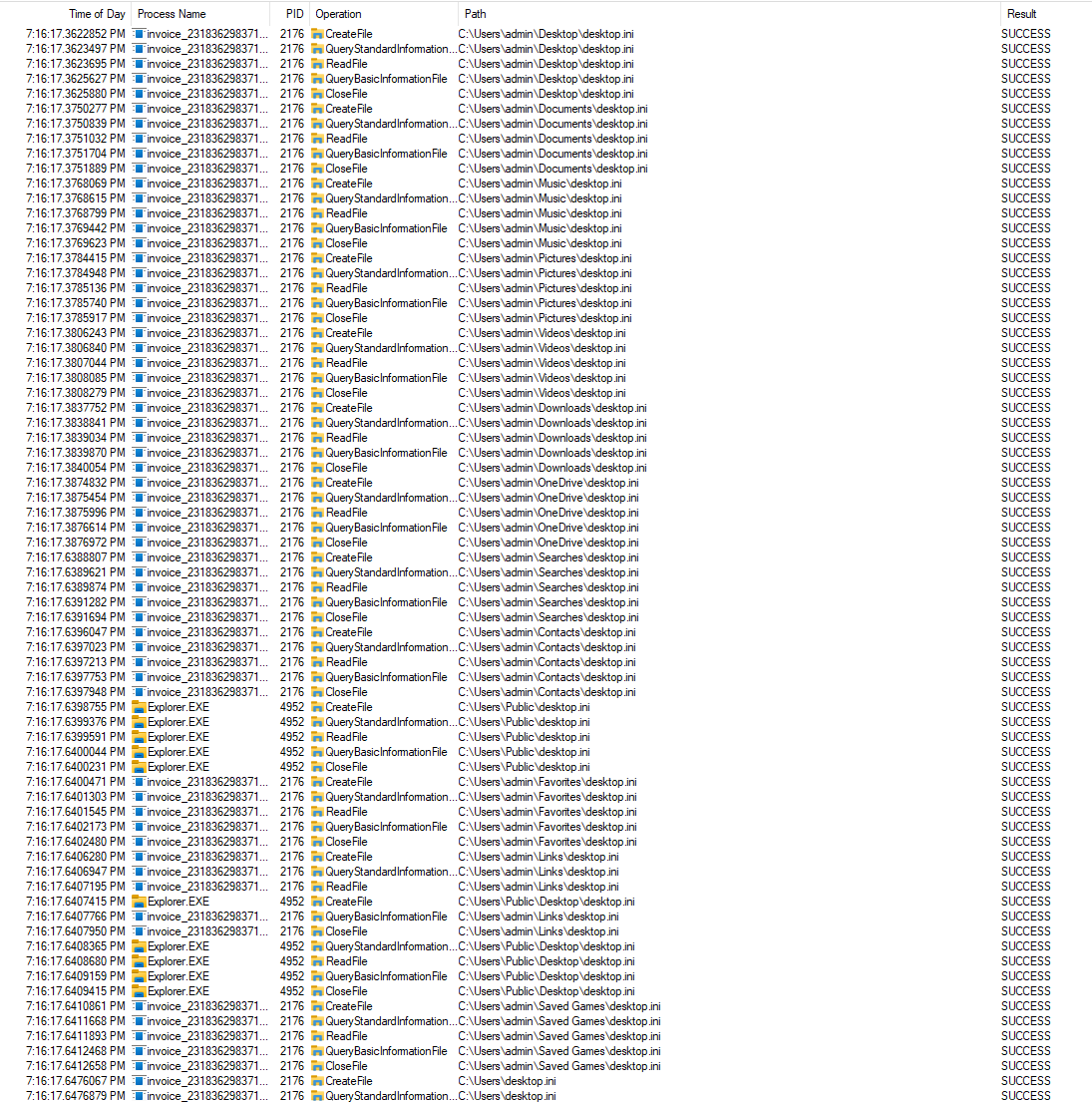

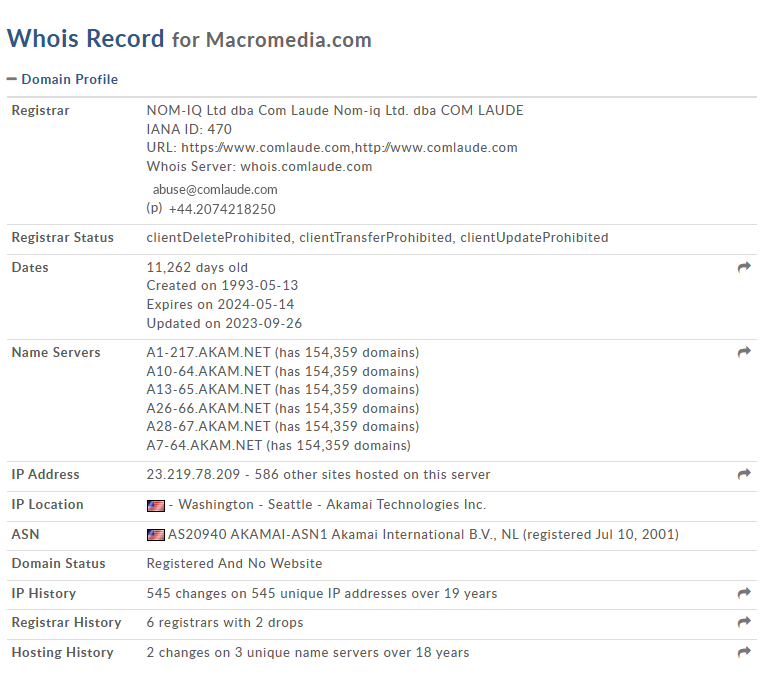

When we visit this domain, we are led to a legitimate website that points to discontinued products. It is my hypothesis that the malware uses this legitimate installer to mask its presence. First it calls on a legitimate installer like the one that once existed on the “fpdownload.macromedia” site, then it modifies it to include malicious payloads or code injections like we established in the Procmon segment. It then edits desktop.ini to conceal its alterations to a legitimate program.

By tampering with this configuration file commonly used for customizing folder appearances, the malware can mask its presence and activity within the system. This tactic allows the malware to evade detection by presenting the modified program as unchanged to the user, effectively camouflaging its malicious modifications. Additionally, manipulating desktop.ini files enable the malware to persistently maintain its foothold on the compromised system, ensuring continued operation while minimizing the risk of detection.

Note the copious number of queries and modifications into desktop.ini files:

Even if our analysis of the packets and processes indicates suspicious or potentially malicious behavior, it’s imperative to exercise caution and verify the IP addresses and domains identified.

Transitioning from the analysis of network packets in Wireshark, our investigation now shifts towards correlating the discovered IP addresses and domains with online databases containing lists of potentially dangerous entities. This step is key for validating the legitimacy of the identified destinations and assessing their threat level. By cross-referencing with known threat intelligence sources, we can gain deeper insights into the broader network infrastructure and potential command-and-control mechanisms utilized by the malicious actors behind the malware, informing our mitigation strategies accordingly.

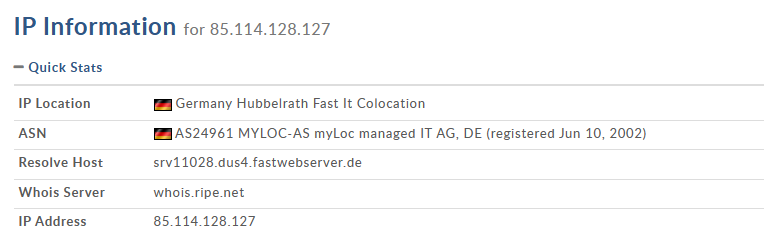

For the IP address, 85.114.128.127, we will perform a DNS lookup, which shows us not only its location, but the resolve host, which was also referenced to in the Wireshark packets:

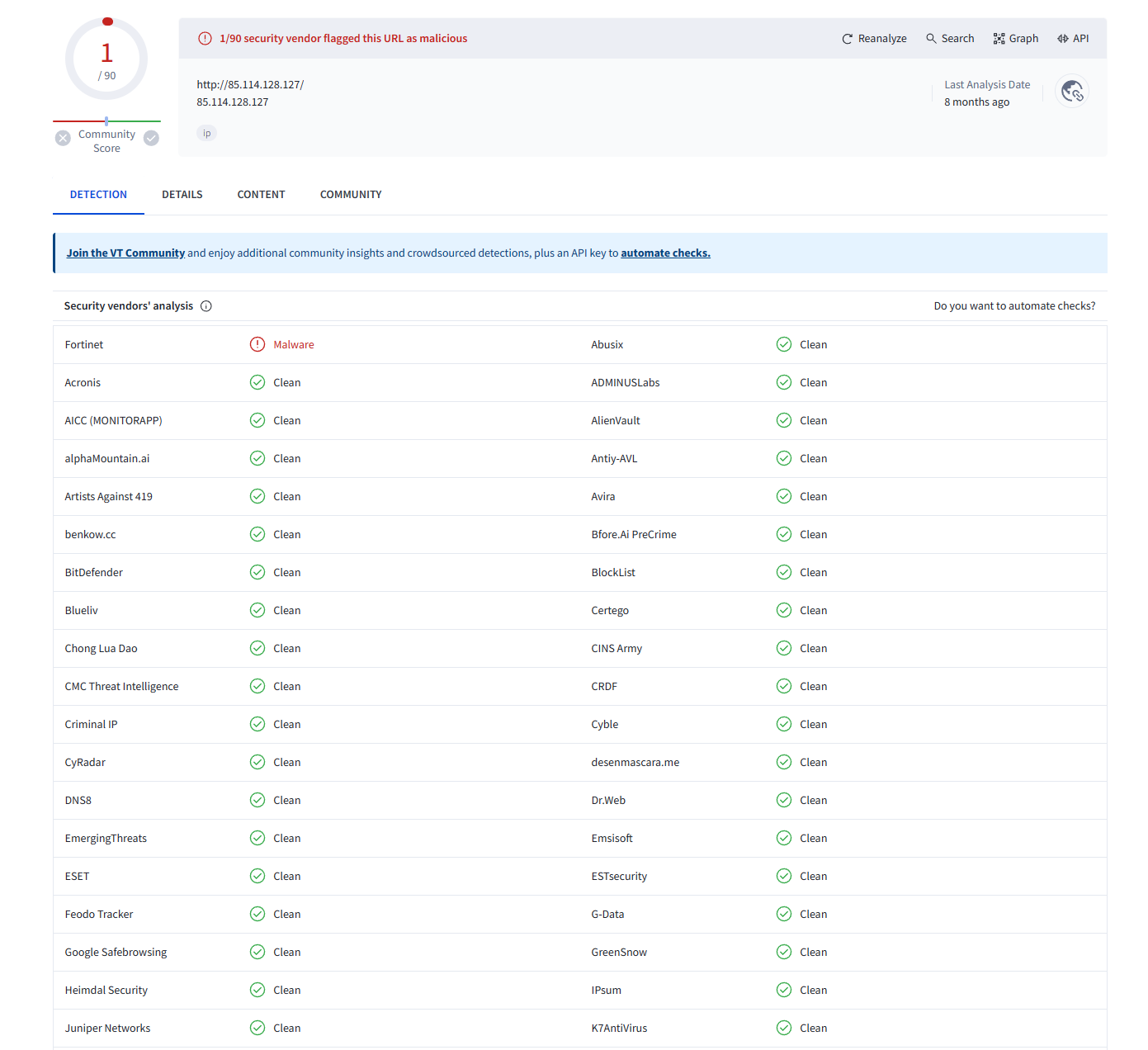

While running this IP address through VirusTotal, there is no direct connection to malicious activity other than one security vendor:

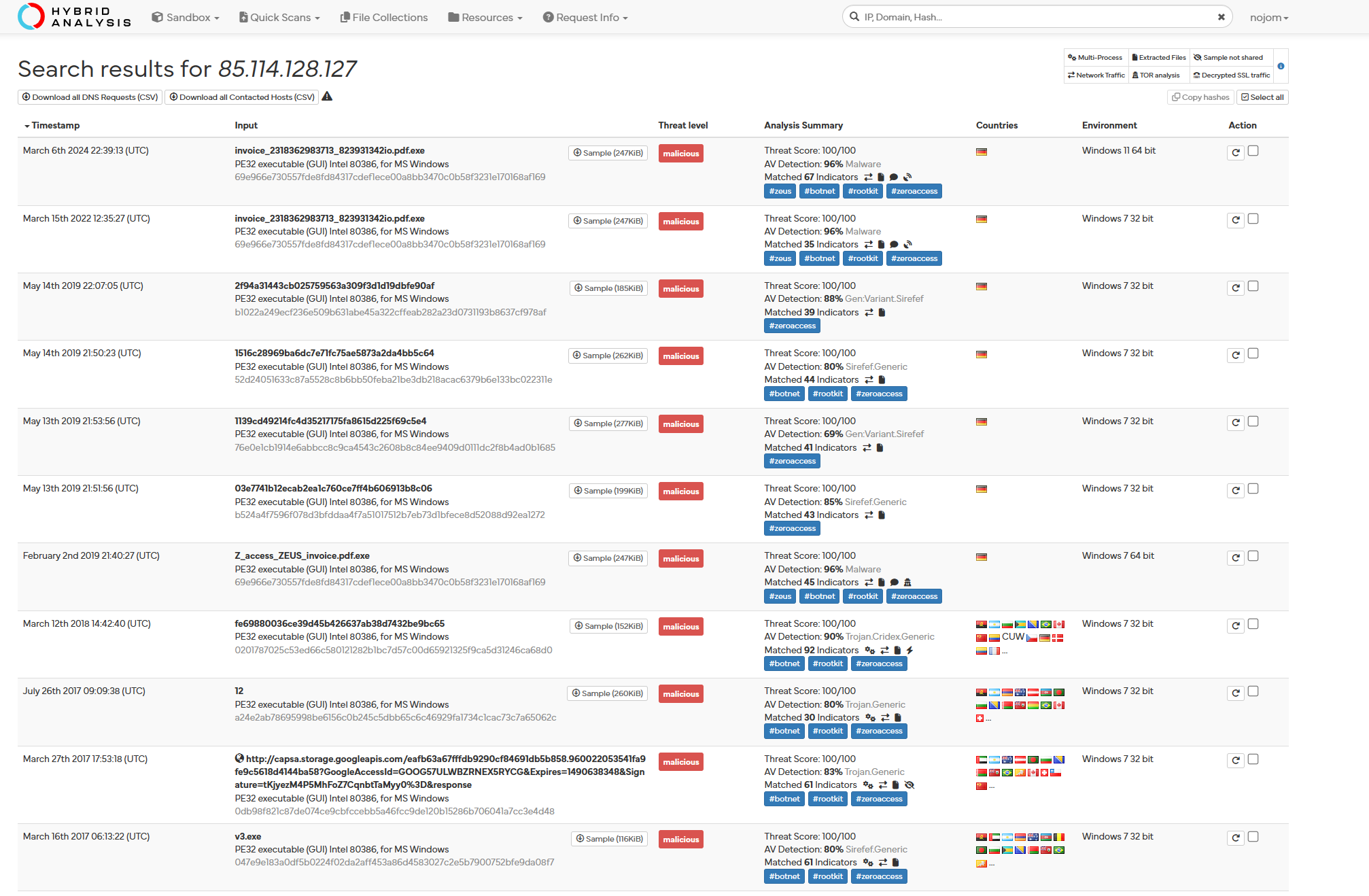

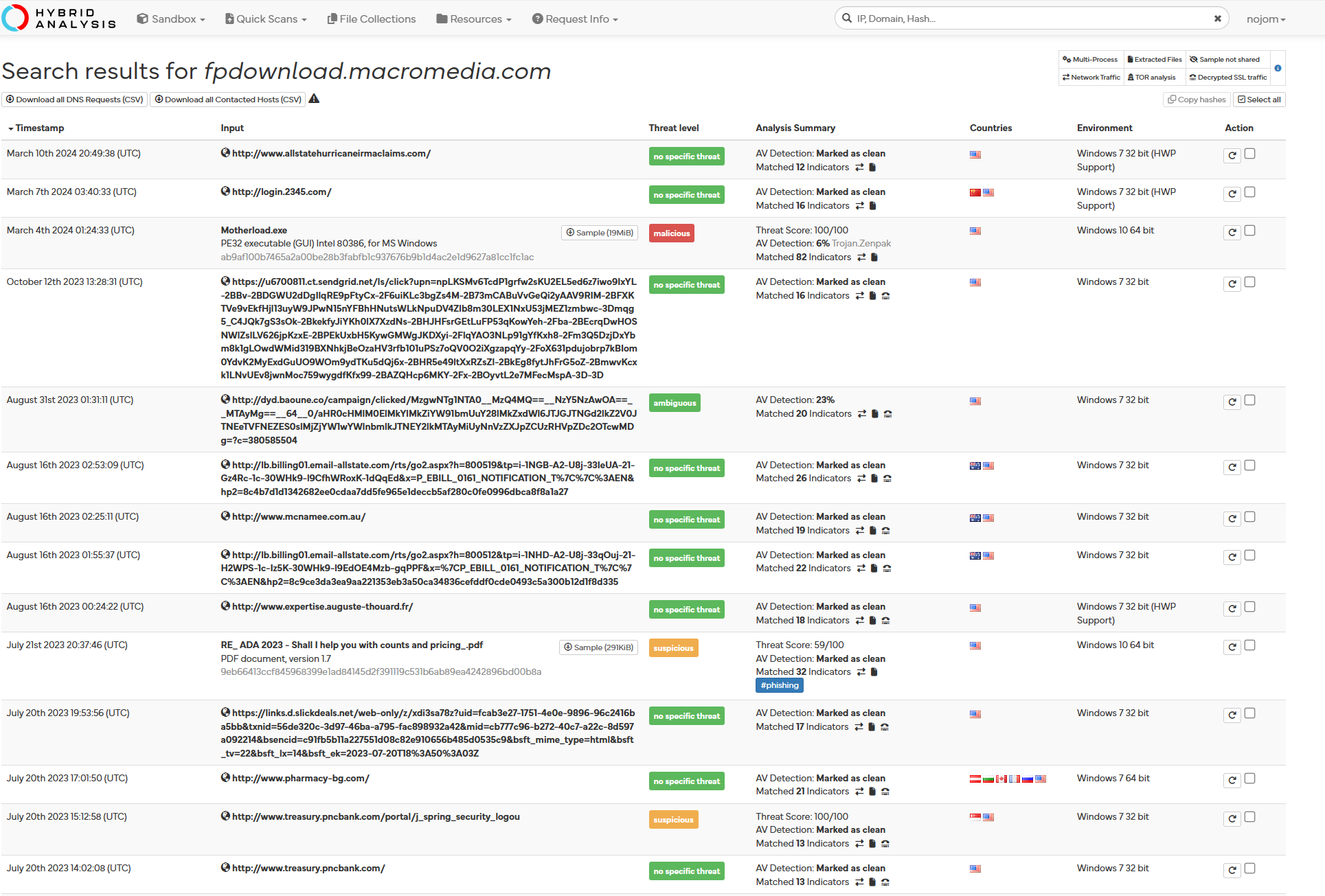

Nevertheless, it is important to cross-reference multiple online databases, such as a Hybrid Analysis. This platform not only provides static and analysis techniques on a submitted file, but also has a search utility that enables analysts to investigate how a specific IP address, domain, or hash has been linked to previous analyses. This functionality allows us to trace the history of the IP address across various malware samples and reports, providing additional context on its involvement in malicious activities:

The appearance of 85.114.128.127 in the search function, linking it to other analyzed malicious files, strengthens the evidence suggesting that the file under scrutiny is indeed malicious. This correlation underscores the recurring involvement of the IP address in malicious activities, reinforcing the assessment of the analyzed file’s nefarious nature.

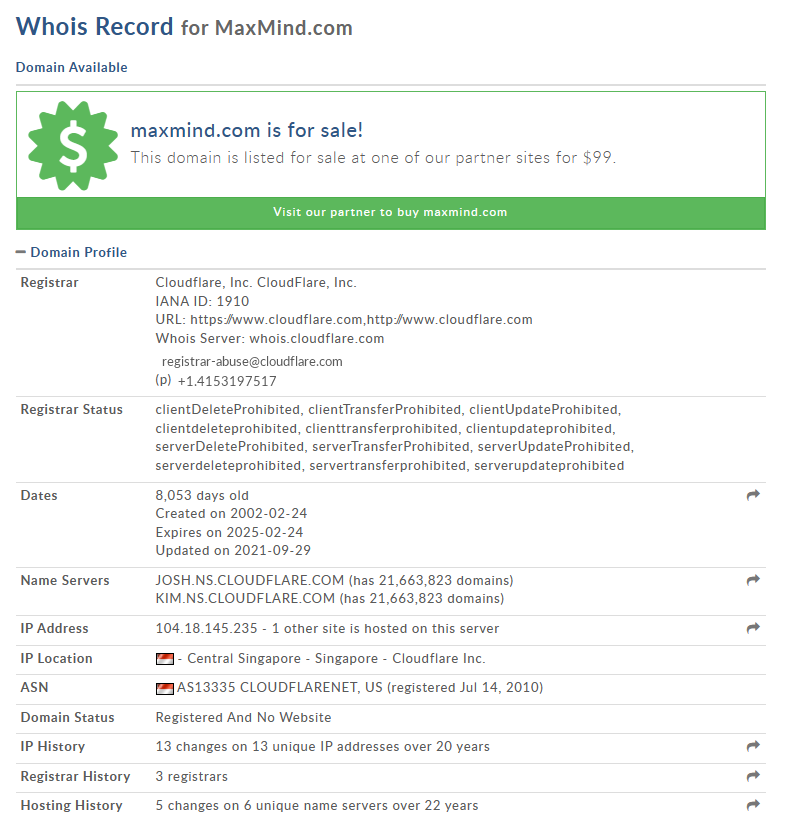

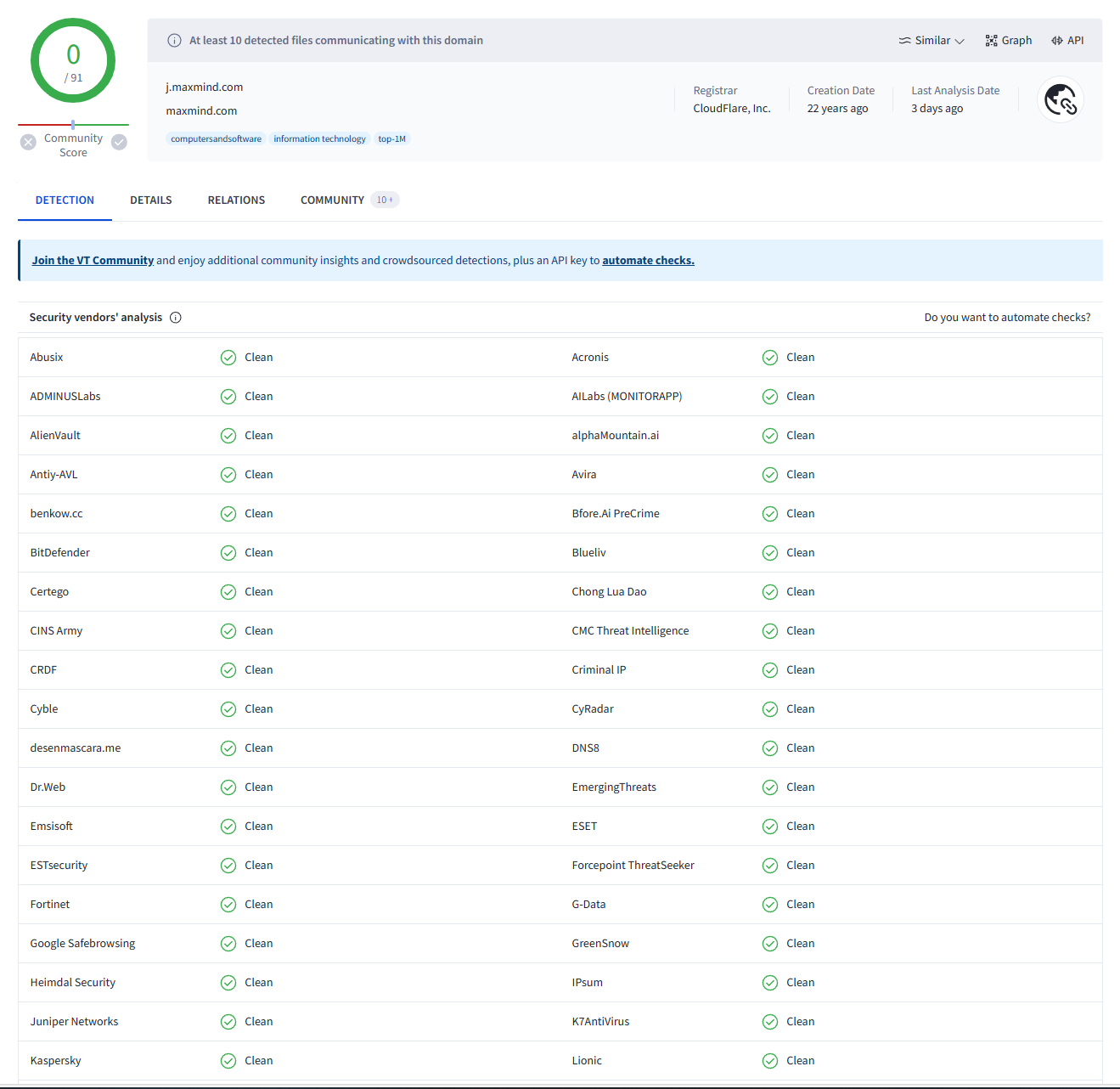

Next, we look at the referenced domain, “j.maxmind.com”:

As we noted in the Wireshark section, Maxmind.com does not inherently perform malicious tasks, but it can be leveraged for malicious activities. This would mean that DNS lookups and even a search through VirusTotal would not provide many promising results:

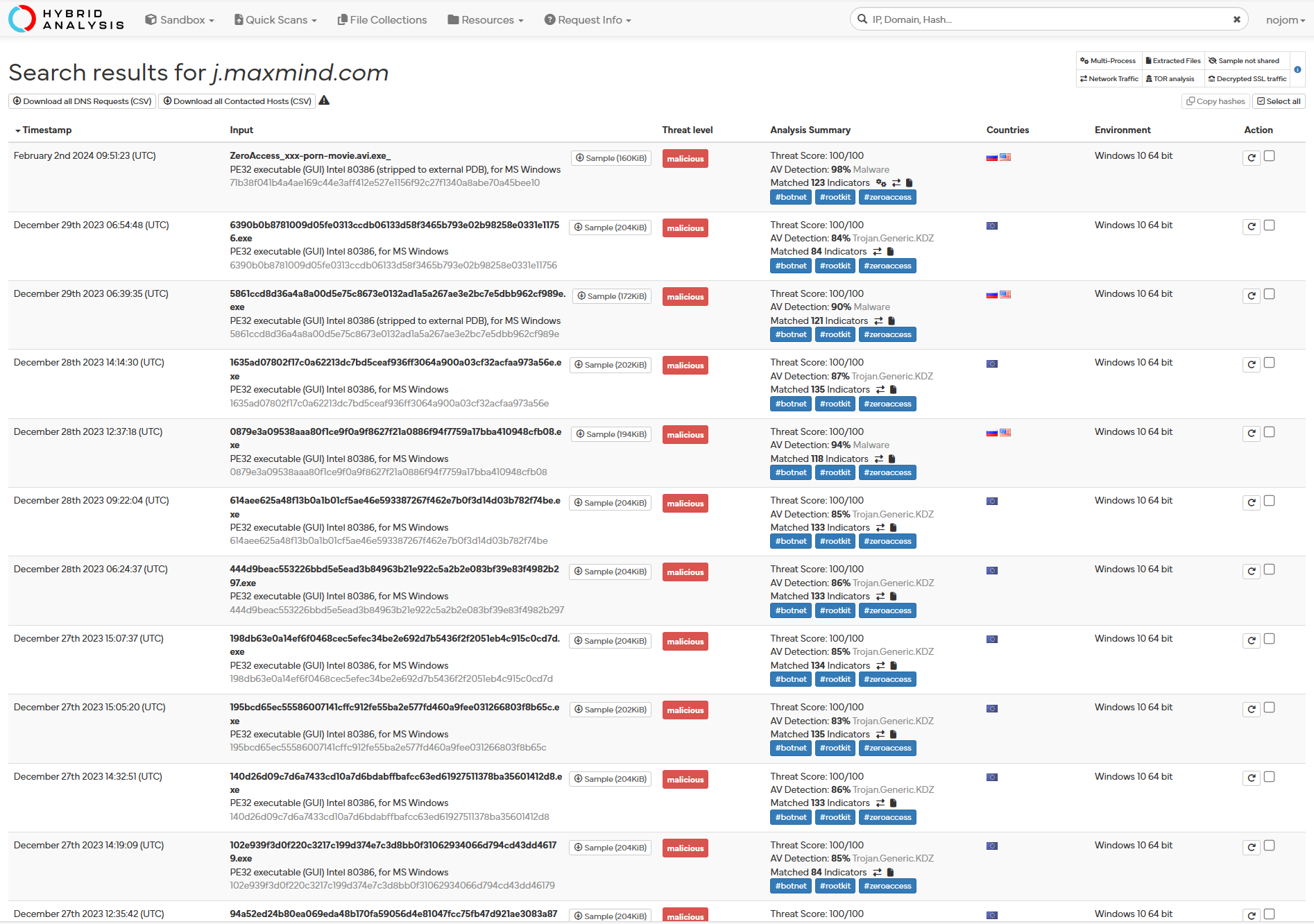

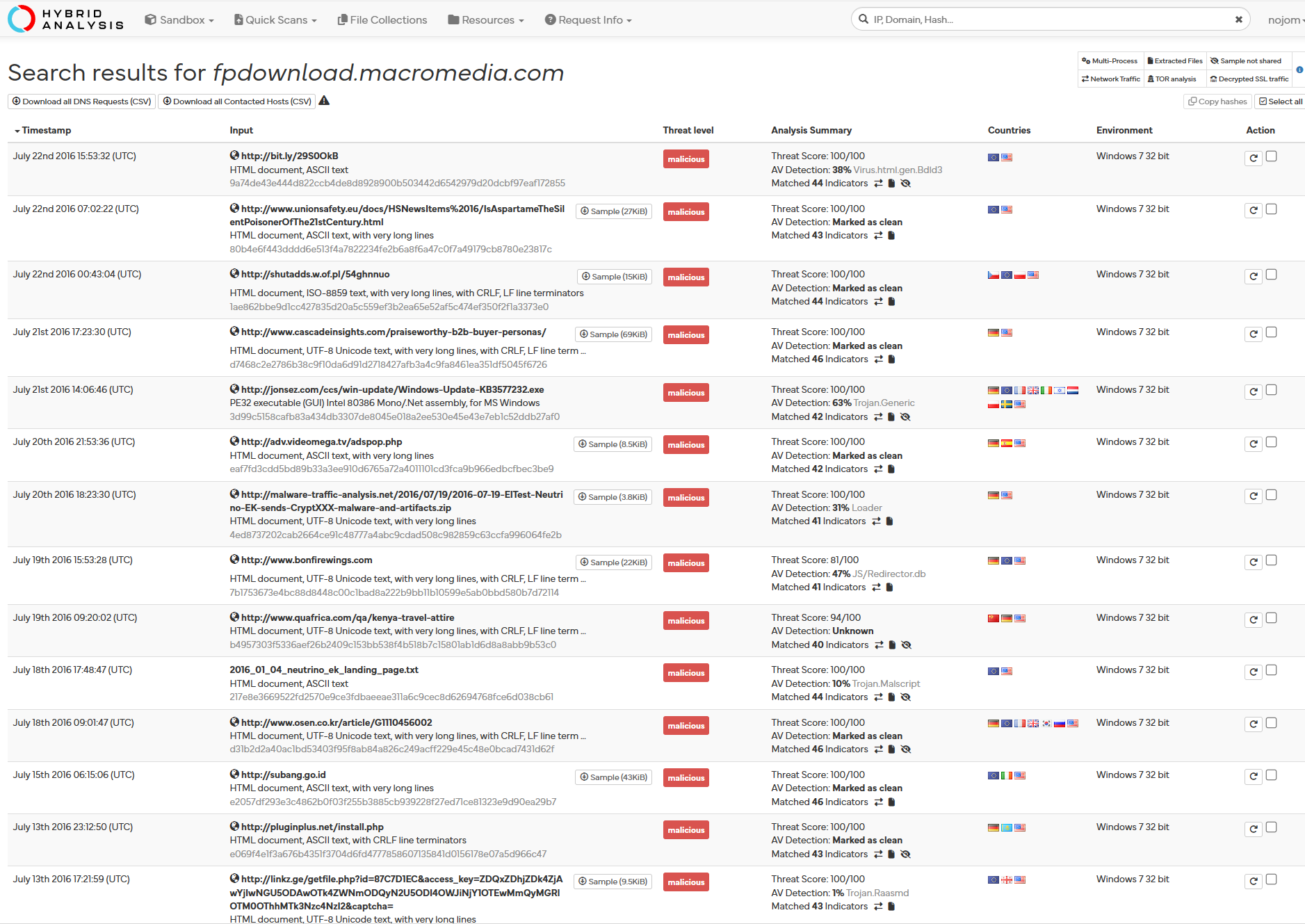

Hybrid Analysis, however, points towards our prior claim:

The inclusion of “j.maxmind.com” in the search function, linking it to other analyzed malicious files, provides additional confirmation of the analyzed file’s malicious nature. The association underscores the involvement of the domain in malicious activities, further solidifying the assessment of the analyzed file as malicious when it is leveraged by the invoice process to gain the victim’s geolocation.

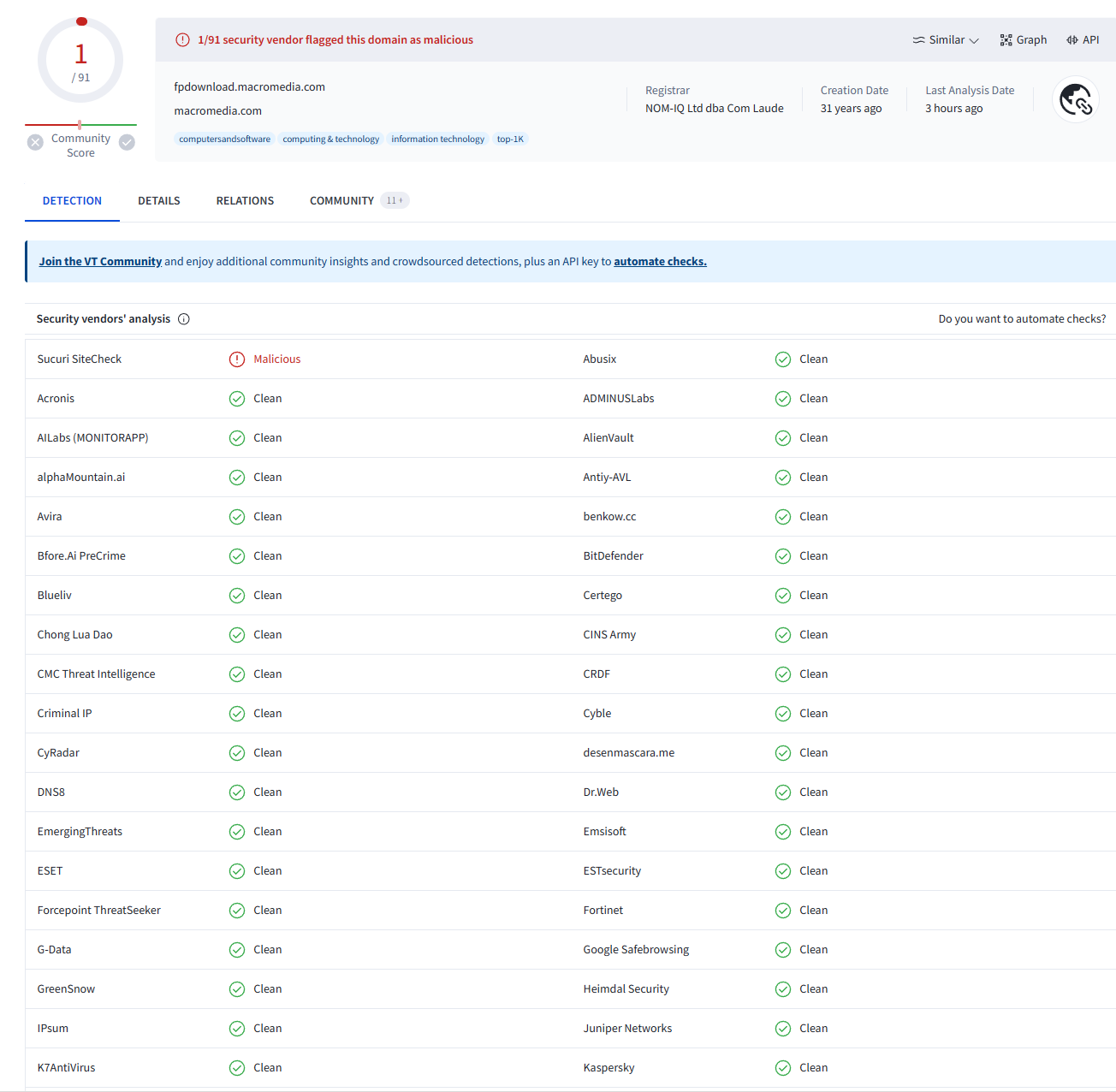

Finally, we can confirm how “fpdwonload.macromedia.com” is a legitimate website, but its use for malicious purposes is still murky:

Virustotal output does not provide conclusive evidence:

Hybrid Analysis output page 1 and page 2:

Although this website can be leveraged for malicious purposes, it can also be completely legitimate. The fact that it redirects to free and discontinued products with support options can allude to it being referenced in outdated, legitimate software or code. But this very fact can be used by malware authors to obfuscate their true intentions, as we hypothesized with the modification of “desktop.ini” files.

Concluding the dynamic analysis conducted through Procmon and Wireshark, we have gained valuable insights into the behavior of the analyzed malware, uncovering suspicious processes, network communications, and registry modifications. Building upon these findings, our focus now shifts to identification and classification using Hybrid Analysis and Yara.

Leveraging Hybrid Analysis’s comprehensive analysis capabilities and Yara’s powerful pattern-matching engine, we aim to further dissect the malware’s characteristics, classify its behavior, and enhance our understanding of its threat profile. This transition marks a crucial phase in our investigation, enabling us to refine our detection methods and strengthen our defenses against similar threats in the future.

Identification and Classification

Hybrid Analysis can be leveraged for malware identification, as it offers an intuitive and powerful platform that democratizes the complex process of malware analysis. By allowing users to effortlessly submit files for examination, it bridges the gap between advanced analytical techniques and practical, actionable insights. Upon submission, Hybrid Analysis deploys a sophisticated blend of static and dynamic analysis within a secure, virtualized environment. This dual approach ensures a thorough examination of the file’s inherent code structure and its behavior upon execution, tracking network communications, file modifications, registry changes, and other critical indicators of malicious activity.

The platform’s strength lies in its comprehensive capability to dissect and document every facet of the file’s interaction with both the system and the network, uncovering hidden payloads, obfuscated code, and covert persistence mechanisms. These detailed reports are invaluable, not only for highlighting the file’s operations and potential impact on affected systems, but also for outlining specific indicators of compromise that can aid in the identification, tracking, and mitigation of threats. By comparing our initial findings with the extensive data provided by Hybrid Analysis, we can validate our observations and deepen our understanding of the threat landscape.

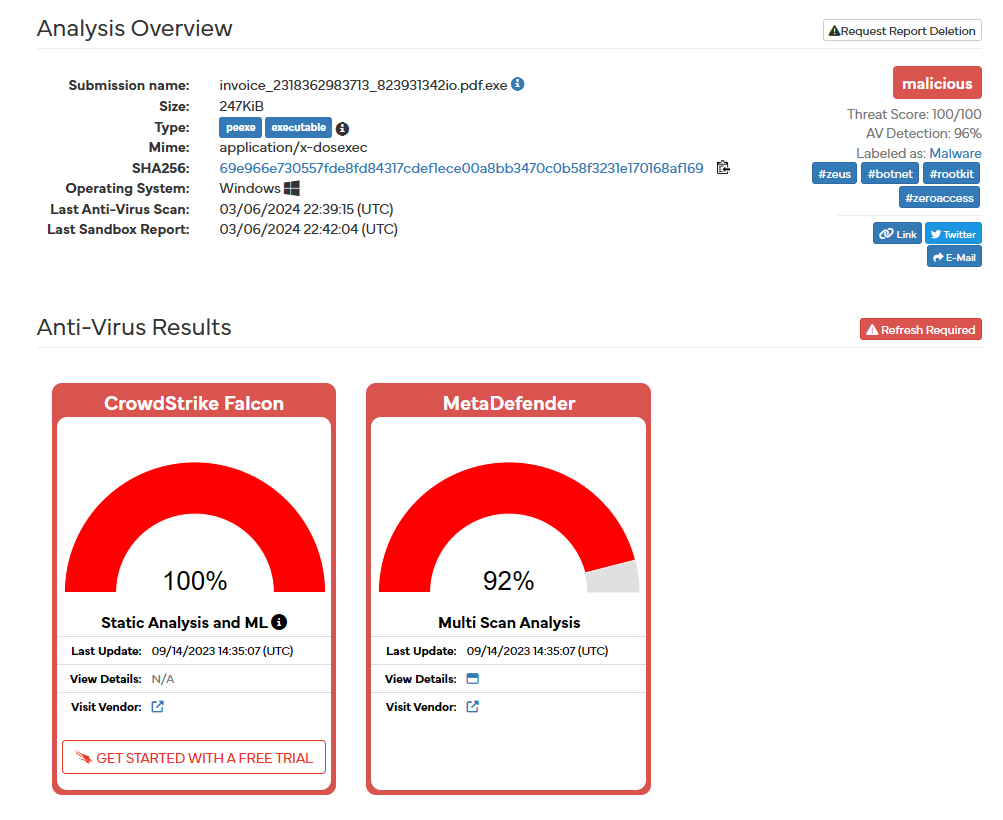

Upon analysis completion, Hybrid Analysis provides a summary of the file and a more in-depth analysis that details a variety of sections. The summary quickly identifies our invoice file as malicious, providing anti-virus results which prove with high certainty the maliciousness:

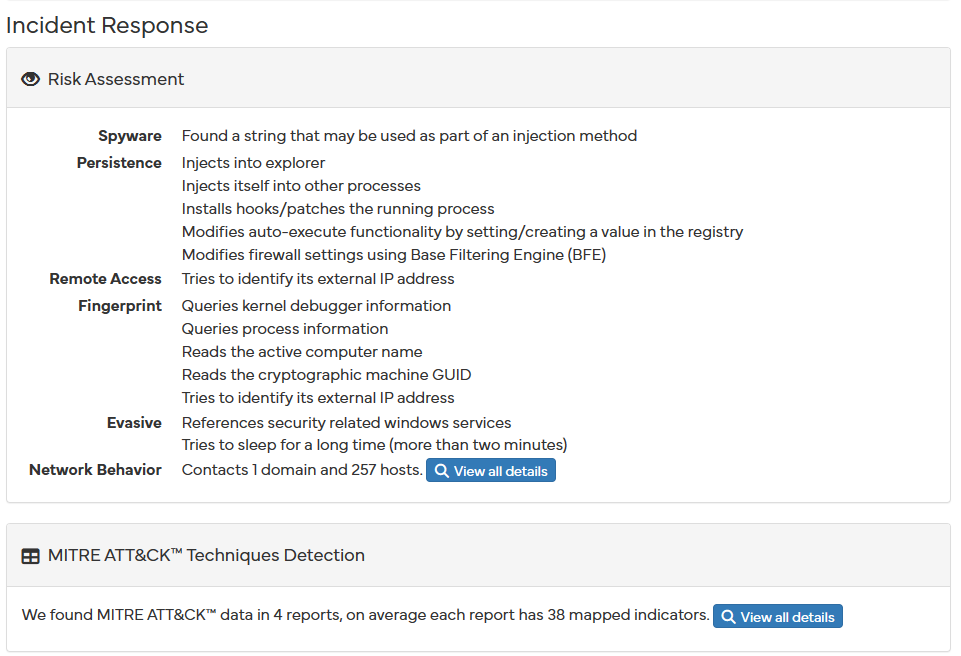

It then provides, if possible, prior analysis that may have included a similar file, followed by a short incident response and a corresponding MITRE ATT&CK techniques detection:

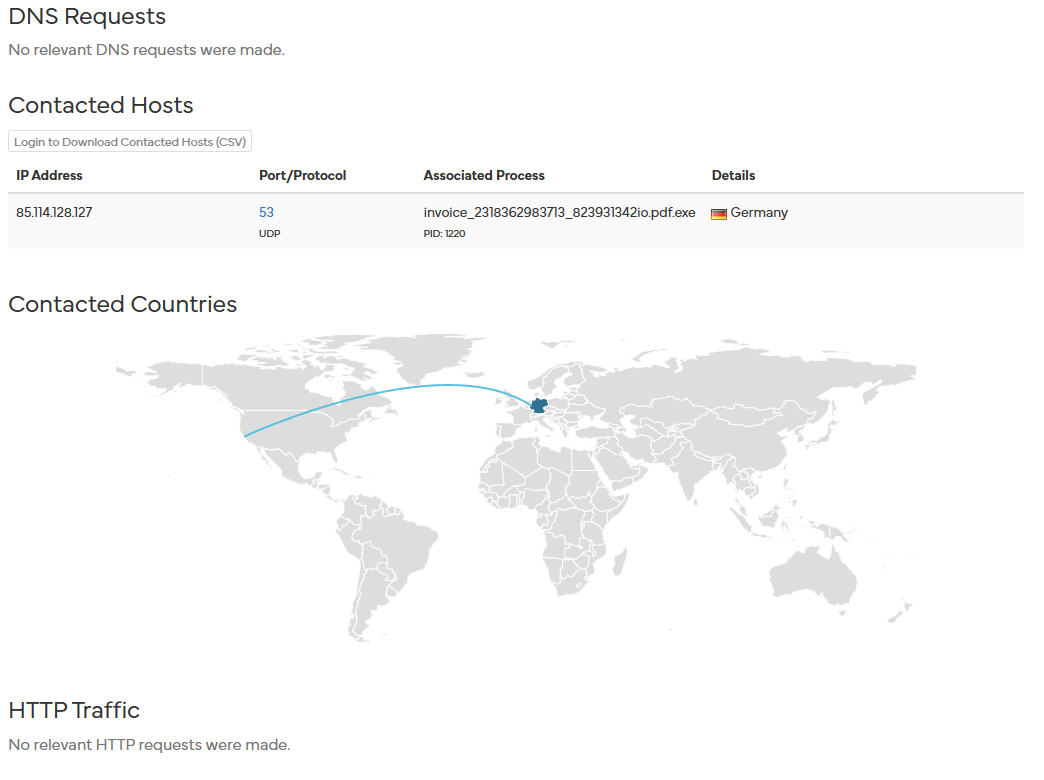

Moving over to the more detailed section we can start to notice similarities between our malware analysis and the one provided:

As noted during our Procmon and Wireshark section, we inferred the connection to a possible host in Germany with an IP of 85.114.128.127. Hybrid Analysis has also noticed the same pattern emerges once the file has been executed.

Interestingly, it denotes that there are no relevant HTTP requests. However, we drew a correlation between the use of a HTTP Get request of a Flash Player Installer and the obfuscation of malware through the modification of desktop.ini files. It is possible that the malware’s intention in hiding its true intentions may have worked in the Hybrid Analysis sandbox.

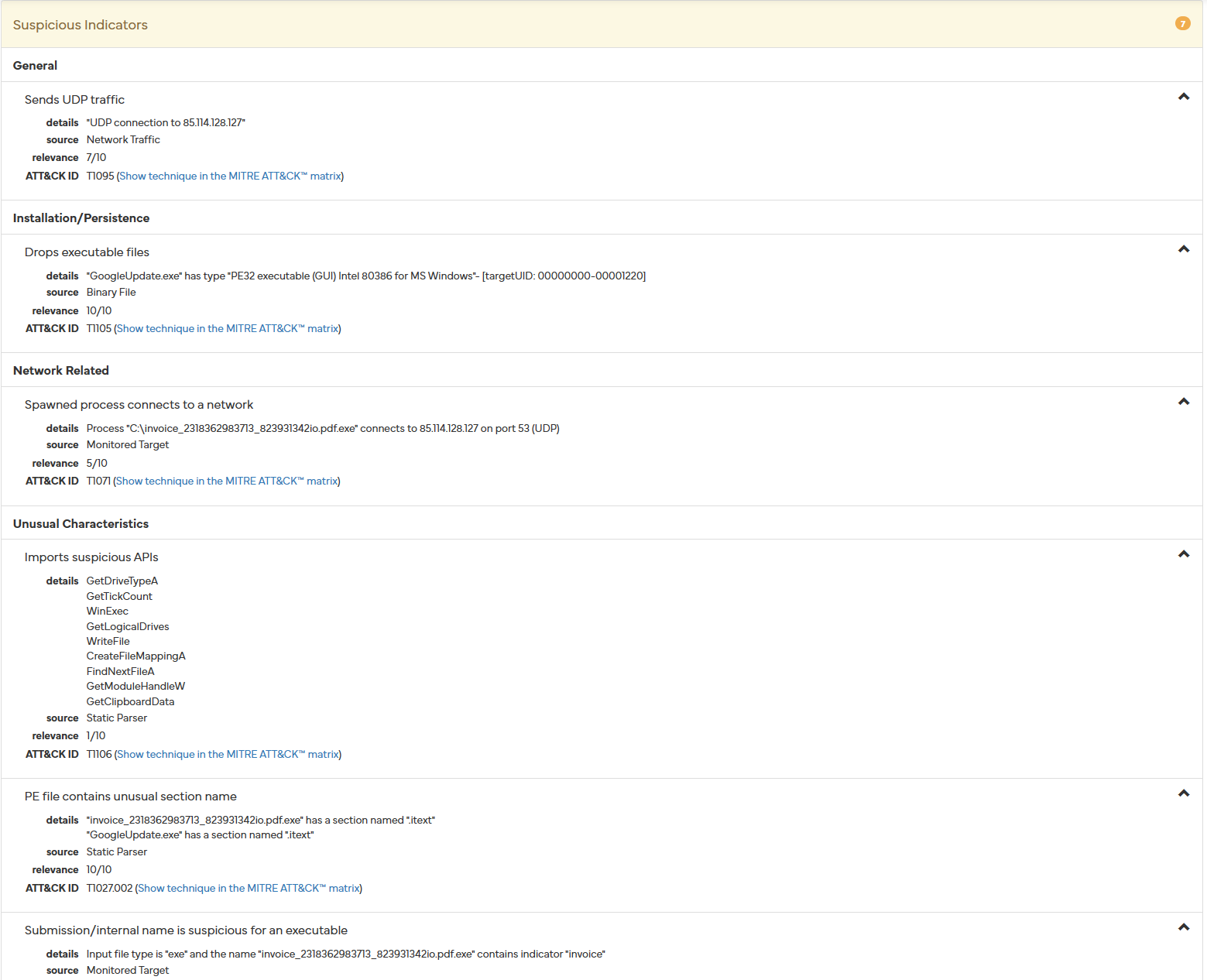

Regardless, there are several suspicious indicators:

- Sends UDP traffic

- Our Procmon and Wireshark analysis confirms UDP traffic

- Installation/Persistence - Drops executable files

- Confirmed by our Procmon analysis by the addition of the GoogleUpdate.exe and its corresponding Windows registry modification: “\run”

- Network Related - Spawned process connects to a network

- We noted that both the “invoice…” and the “InstallFlashPlayer.exe” processes reached out through UDP to a unknown IP address

- Unusual characteristics - Imports suspicious APIs

- During our static analysis we noted various problematic APIs

- PE file contains unusual section name

- While we did note this file and it’s entropy, we did not note its unusual section name

- Submission/internal name is suspicious for an executable

- While this may not be noticed by a laymen, the extension name of this file is highly problematic and points to its malicious intent and should be noted

Our meticulous dynamic analysis through Procmon and Wireshark, alongside our static examination, closely aligns with the findings presented by Hybrid Analysis, reinforcing the accuracy and thoroughness of our investigative approach. Key similarities include the observation of UDP traffic, a detail of our analysis confirmed through both network and process monitoring, which Hybrid Analysis also noted. Further, the installation and persistence mechanisms identified by Hybrid Analysis, through the dropping of executable files and modifications to Windows registry keys, were directly observed in our Procmon analysis, specifically with the creation of “GoogleUpdate.exe” and alterations within the “\run” registry.

Additionally, the network behaviors observed, such as the spawned process “invoice” and “InstallFlashPlayer.exe” initiating UDP communications with unknown IP addresses, were paralleled in both analyses, emphasizing the malware’s network engagement. Although our static analysis flagged various suspicious APIs, corroborating Hybrid Analysis’s findings on unusual characteristics, we missed noting the peculiar section name with the PE file - a point Hybrid Analysis highlighted. Moreover, both analyses identified the submission/internal name of the executable as suspicious, a detail that blatantly points to the file’s malicious intent. The convergence of findings not only validates our investigate methods but also underscores the comprehensive nature of Hybrid Analysis as a tool for deepening our understanding of malware’s intricate behaviors and intentions.

YARA stands as a powerful tool in the realm of cybersecurity, designed for the classification and identification of malware samples based on binary or textual patterns. This rule-based approach allows analysts to craft specific criteria, capturing the essence of a malware’s behavior or characteristics in a set of rules. These rules can match against file contents, binary sequences, or textual patterns found within a sample, enabling the detection of both known threats and variants of existing malware. By leveraging YARA, cybersecurity professionals can efficiently sift through vast datasets, pinpointing suspicious files with precision. This methodology not only streamlines the process of malware detection but also enhances the ability to adapt and respond to evolving cyber threats, making YARA an indispensable tool in the ongoing battle against malware.

YARA rules typically consist of three sections:

- Meta Information: Provides metadata about the rule, including description, authorship, and creation date

- Strings Section: Defines the text or binary patters that the rule searches for within files that are associated with the malware

- Conditions: Specifies the conditions that must be met for the rule to trigger

For our custom YARA rule we will include some strings that were flagged in PEstudio, along with some binary sequences that can be viewed with Ghidra or Cutter:

rule Zeus_Banking {

meta:

description = "YARA rule for detecting Zeus Banking Trojan"

author = "Randy Ramirez"

date = "2024-03-15"

strings:

$str1 = "AllowSetForegroundWindow"

$str2 = "DdeQueryNextServer"

$str3 = "EnumClipboardFormats"

$str4 = "FindNextFileA"

$str5 = "GetAsyncKeyState"

$str6 = "GetClipboardData"

$str7 = "GetClipboardOwner"

$str8 = "GetConsoleAliasExesLengthW"

$hex_string1 = { 47 68 69 73 47 6f 6f 64 48 6f 77 6c 43 6f 6f 6e 43 69 67 73 63 61 74 65 67 65 64 00 }

$hex_string2 = { 48 6f 67 67 53 6f 6f 6e 4c 61 73 73 74 77 61 65 4e 61 70 65 43 65 69 6c 42 61 77 6c 73 63 6f 70 64 75 62 00 }

condition:

3 of ($str*) and $hex_string1 and $hex_string2

}

With this condition, a check for the presence of at least four of the defined strings and both defined binary sequences would need to be passed to identify this Zeus Banking Trojan. More strings and binary sequences can be added to increase the robustness of the YARA rule.

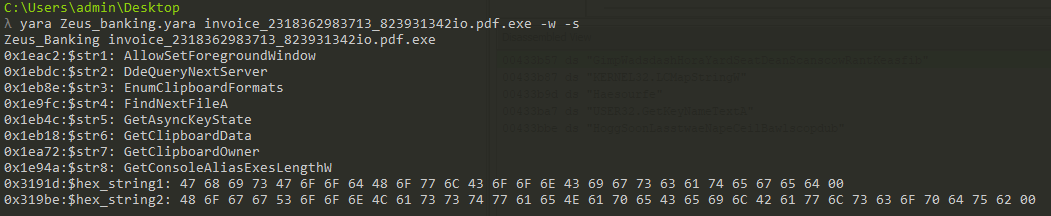

To test the efficacy of our newly establish rule, we can run YARA from the Cmdr, a console emulator for Windows:

yara Zeus_banking.yara invoice_2318362983713_823931342io.pdf.exe -w -s

// Zeus_banking.yara = YARA rule file

// invoice... = file being scanned for matches

// -w = supress warnings

// -s = print matching strings

The following is outputted:

This means that the printed strings are ones that have matched the strings specified in the YARA rules, confirming our rule, and hereby concluding our malware analysis on the Zeus Banking Trojan.

In pursuit of our objective to analyze the malware thoroughly, we’ve utilized a comprehensive array of static and dynamic tools, alongside identification and classification tools. Static analysis tools such as VirusTotal, PEStudio, Floss, Capa, Cutter, and Ghidra scrutinized the malware’s binary code, identifying suspicious patterns, APIs, and characteristics. Dynamic analysis tools including Inetsim, Wireshark, and Procmon allowed us to observe the malware’s behavior in a controlled environment, uncovering its network communications, system interactions, and persistence mechanism.

Furthermore, by utilizing identification and classification tools like YARA and Hybrid Analysis, we refined our analysis, enabling us to categorize and understand the malware’s nature and potential threats more effectively. This comprehensive approach displays our proficiency in malware analysis and our ability to utilize a diverse toolkit to uncover and mitigate cybersecurity risks effectively. Through our detailed report, we were able to communicate our technical findings, highlighting our expertise in malware research and analysis while providing actionable insights for enhancing cybersecurity defenses.

Feel free to check out my other projects for more detailed guides!